Neanderthal bones: Signs of their sex lives

PIERRE ANDRIEU/AFP via Getty Images

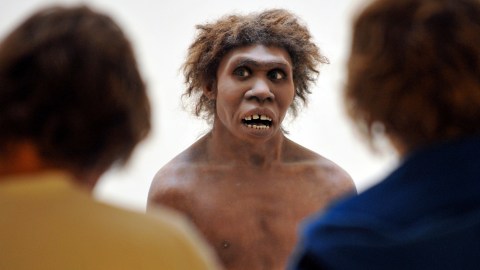

In a cave tucked into the limestone hills of the Asturias region of Spain, there lie the remains of a group of 13 Neanderthals that date to between 50,600 and 47,300 years ago.

The site is infamous among anthropologists who study the Paleolithic period for the evidence of what appears to be the massacre and possible cannibalization of a family: Their bones seem to have been hacked at by stone tools and hammers, probably by another group of Neanderthals, to remove their flesh and marrow.

But more importantly, for this story, those bones also reveal something of the sex life of the cave’s inhabitants. Anomalies and deformations, along with the DNA buried within their bones, suggest that the members of this group (and their parents) were mating with their close kin.

Lately, much news from the field of paleoarchaeology and anthropology has centered on Neanderthal bedfellows. You would be forgiven for thinking that paleoanthropologists think about little other than paleo-sex. Within the past several years, genetic evidence has emerged that Neanderthals interbred on more than one occasion with both anatomically modern humans and our newfound ancient relative, the Denisovans. One finger bone fragment from Denisova Cave in Siberia is now famous for belonging to a teenage girl who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

But evidence also shows that while some Neanderthals were apparently breeding well outside of the family group, some were also finding mates much closer to home.

In the remains from El Sidrón Cave, paleoanthropologist Luis Ríos and colleagues found 17 examples of congenital anomalies—structural malformations of various body parts that occur while an individual is developing in the womb.

One young El Sidrón individual, for example, had an oddly shaped patella, the bone that forms the kneecap: It had three lobes rather than just one. This Neanderthal probably had a limp. An adult male in the same cave had a markedly narrow nasal passage and a “retained deciduous mandibular canine,” writes Ríos and his co-authors—this adult Neanderthal never lost one of his lower canine baby teeth. That tooth developed a painful cyst, which left its mark on the bone of his jaw. Microscopic striations on the tooth itself suggest that he coped with the pain by avoiding chewing on that side of his mouth.

One possible explanation for these skeletal abnormalities is that they resulted from extremely stressful environmental conditions, such as brutally cold weather and scarce food. A pregnant mother experiencing a lot of physical stress and nutritional deprivation might give birth to an infant with some of the same conditions seen at El Sidrón.

Inbreeding leads to a problematically small gene pool

But DNA tests from these bones indicate that inbreeding and a small population size were likely factors contributing to the physical peculiarities in this family. The 13 El Sidrón Neanderthals share much longer segments of their DNA than would be expected if they were the offspring of non-relatives.

Genetically, the three adult males in the group were closely related enough to be brothers, cousins, or uncles, while the four adult females in the group came from three distinct genetic lines. While all individuals were likely distantly related to one another (think third or fourth cousins), it is likely that the males exchanged females with another local, slightly less closely related group.

Today inbreeding carries connotations of “kissing cousins” or intimacy between even closer familial relations. But the term simply means mating between relatives, which increases the number of common ancestors in a family tree and the likelihood of inheriting deleterious genes from those common ancestors. Even third or fourth cousins are genetically similar enough for issues to arise.

The younger El Sidrón individuals (ranging in age from 5 to 15 years of age, along with one infant) were likely the offspring of at least some of the adults. At least one of these children, the young male mentioned above, possessed skeletal malformations that were likely passed down from parents who were fairly closely related.

The tangled familial ties of the El Sidrón Neanderthals are not a unique situation; DNA evidence from other Neanderthals elsewhere in Eurasia also shows elevated instances of shared DNA segments around this time, suggesting that mating between individuals who shared recent ancestors was fairly frequent, and possibly unavoidable, if local populations were small.

In general, inbreeding leads to a problematically small gene pool. Rare harmful traits that might disappear in larger populations tend to be amplified if close kin interbreed. Yet inbreeding has happened throughout human history, especially in the royal families of different cultures. Just look at the Habsburg family line in Spain or the royal families of Ancient Egypt to see the effects of keeping family bloodlines “pure.”

Neanderthals were not the only ancient hominins to mate with their close relatives. Anatomically modern humans have also been found with skeletal evidence of inbreeding, such as abnormally bowed thigh bones, deformed arm bones, and even a case of a toddler with a swollen brain case consistent with hydrocephalus.

At the time that these congenital malformations appear, between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, modern humans were traveling out of Africa. They fanned out across vast geographical regions, and, at times, were quite isolated from one another. Populations might have been separated by hundreds of kilometers at a time, only rarely encountering one another. This might be a simple reason why inbreeding occurred: Pickings were slim.

During the time that the El Sidrón Neanderthal family occupied their cave, it is likely that they were also fairly isolated. Their mating patterns probably had much more to do with small population size and low population density than any sort of cultural practice. There is no way to know if cultural taboos against mating with close relatives existed back then.

Interestingly, most of the individuals in the El Sidrón family group lived well past infancy despite physical conditions that, in some cases, would have made it difficult for them to get around and perform their day-to-day tasks. This family cared for one another, sharing physical burdens and helping each other to survive. Their relations, and their care, are recorded in their bones.

This column is part of an ongoing series about the Neanderthal body: a head-to-toe tour. See our interactive graphic.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.