‘A Glitch in the Matrix’ documentary explores the dark side of simulation theory

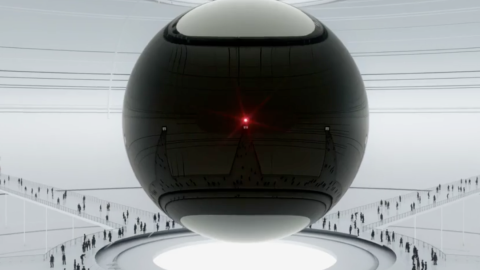

Credit: A Glitch in the Matrix / Rodney Ascher

- Simulation theory proposes that our world is likely a simulation created by beings with super-powerful computers.

- In "A Glitch in the Matrix," filmmaker Rodney Ascher explores the philosophy behind simulation theory, and interviews a handful of people who believe the world is a simulation.

- "A Glitch in the Matrix" premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival and is now available to stream online.

Are you living in a computer simulation?

If you’ve spent enough time online, you’ve probably encountered this question. Maybe it was in one of the countless articles on simulation theory. Maybe it was during the chaos of 2020, when Twitter users grew fond of saying things like “we’re living in the worst simulation” or “what a strange timeline we’re living in.” Or maybe you saw that clip of Elon Musk telling an audience at a tech conference that the probability of us not living in a simulation is “one in billions.”

It might sound ludicrous. But Twitter memes and quotes from “The Matrix” aside, simulation theory has some lucid arguments to back it up. The most cited explanation came in 2003, when Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom published a paper claiming at least one of the following statements is true:

- The human species is very likely to go extinct before reaching a “posthuman” stage

- Any posthuman civilization is extremely unlikely to run a significant number of simulations of their evolutionary history (or variations thereof)

- We are almost certainly living in a computer simulation

The basic idea: Considering that computers are growing exponentially powerful, it’s reasonable to think that future civilizations might someday be able to use supercomputers to create simulated worlds. These worlds would probably be populated by simulated beings. And those beings might be us.

In the new documentary “A Glitch in the Matrix”, filmmaker Rodney Ascher sends viewers down the rabbit hole of simulation theory, exploring the philosophical ideas behind it, and the stories of a handful of people for whom the theory has become a worldview.

The film features, for example, a man called Brother Laeo Mystwood, who describes how a series of strange coincidences and events — a.k.a “glitches in the matrix” — led him to believe the world is a simulation. Another interviewee, a man named Paul Gude, said the turning point for him came in childhood when he was watching people sing at a church service; the “absurdity of the situation” caused him to realize “none of this is real.”

A Glitch in the Matrix – Official Trailerwww.youtube.com

But others have darker reactions after coming to believe the world is a simulation. For example, if you believe you’re in a simulation, you might also think that some people in the simulation are less real than you. A few of the film’s subjects describe the idea of other people being “chemical robots” or “non-player characters,” a video-game term used to describe characters who behave according to code.

The documentary’s most troubling sequences features the story of Joshua Cooke. In 2003, Cooke was 19 years old and suffering from an undiagnosed mental illness when he became obsessed with “The Matrix.” He believed he was living in a simulation. On a February night, he shot and killed his adoptive parents with a shotgun. The murder trial spawned what’s now known as the “Matrix defense,” a version of the insanity defense in which a defendant claims to have been unable to distinguish reality from simulation when they committed a crime.

Of course, Cooke’s case lies on the extreme side of the simulation theory world, and there’s nothing inherently nihilistic about simulation theory or people who believe in it. After all, there are many ways to think about simulation theory and its implications, just as there are many different ways to think about religion.

And as with religion, a key question in simulation theory is: Who created the simulation and why?

In his 2003 paper, Bostrom argued that future human civilizations might be interested in creating “ancestor simulations,” meaning that our world might be a simulation of a human civilization that once existed in base reality; it’d be a way for future humans to study their past. Other explanations range from the simulation being some form of entertainment for future humans, to the simulation being the creation of aliens.

“If this is a simulation, there’s sort of a half dozen different explanations for what this is for,” Ascher told Big Think. “And some of them are completely opposite from one another.”

To learn more about simulation theory and those who believe in it, we spoke to Ascher about “A Glitch in the Matrix”, which premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival and is now available to stream online. (This interview has been lightly edited for concision and clarity.)

Rodney Ascher / “A Glitch in the Matrix”

Throughout 2020, many people seemed to talk about the world being a simulation, especially on Twitter. What do you make of that?

I see that just as sort of evidence of how deep the idea [of simulation theory] is penetrating our culture. You know, I’m addicted to Twitter, and everyday something strange happens in the news, and people make some jokes about, “This simulation is misfiring,” or, “What am I doing in the dumbest possible timeline?”

I enjoy those conversations. But two things about them: On the one hand, they’re using simulation theory as a way to let off steam, right? “Well, this world is so absurd, perhaps that’s an explanation for it,” or, “Maybe at the end of the day it doesn’t matter that much because this isn’t the real world.”

But also, when you talk about the strange or horrifying, or bizarre unlikely things that happen as evidence [for the simulation], then that begs the question, well what is the simulation for, and why would these things happen? They could be an error or glitch in the matrix. […] Or those strange things that happen might be the whole point [of the simulation].

How do you view the connections between religious ideas and simulation theory?

I kind of went in [to making the film] thinking that this was, in large part, going to be a discussion of the science. And people very quickly went to, you know, religious and sort of ethical places.

I think that connection made itself clearest when I talked to Erik Davis, who wrote a book called “Techgnosis“, which is specifically about the convergence of religion and technology. He wanted to make it clear that, from his point of view, simulation theory was sort of a 21st-century spin on earlier ideas, some of them quite ancient.

To say that [religion and simulation theory] are exactly the same thing is sort of pushing it. […] You could say that if simulation theory is correct, and that we are genuinely in some sort of digitally created world, that earlier traditions wouldn’t have had the vocabulary for that.

So, they would have talked about it in terms of magic. But by the same token, if those are two alternative, if similar, explanations for how the world works, I think one of the interesting things that it does is that either one suggests something different about the creator itself.

In a religious tradition, the creator is this omnipotent, supernatural being. But in simulation theory, it could be a fifth-grader who just happens to have access to an incredibly powerful computer [laughs].

Rodney Ascher / “A Glitch in the Matrix”

How did your views on simulation theory change since you started working on this documentary?

I think what’s changed my mind the most in the course of working on the film is how powerful it is as a metaphor for understanding the here-and-now world, without necessarily having to believe in [simulation theory] literally.

Emily Pothast brought up the idea of Plato’s cave as sort of an early thought experiment that is kind of resonant of simulation theory. And she expands upon it, talking about how, in 21st-century America, the shadows that we’re seeing of the real world are much more vivid. You know, the media diets that we all absorb, that are all reflections of the real world.

But the danger that the ones you’re seeing aren’t accurate—whether that’s just signal loss from mistakes made by journalists working in good faith, or whether it’s intentional distortion by somebody with an agenda—that leads to a really provocative idea about the artificial world, the simulated world, that each of us create, and then live in, based on our upbringing, our biases, and our media diet. That makes me stop and pause from time to time.

Do you see any connections between mental illness, or an inability to empathize with others, and some peoples’ obsession with simulation theory?

It can certainly lead to strange, obsessive thinking. [Laughs] For some reason, I feel like I have to defend [people who believe in simulation theory], or qualify it. But you can get into the same sort of non-adaptive behavior obsessing on, you know, the Beatles or the Bible, or anything. [Charles] Manson was all obsessed on “The White Album.” He didn’t need simulation theory to send him down some very dark paths.

Credit: K_e_n via AdobeStock

Why do you think people are attracted to simulation theory?

You might be attracted to it because your peer group is attracted to it, or people that you admire are attracted to it, which lends it credibility. But also like, just the way you and I are talking about it now, it’s a juicy topic that extends in a thousand different ways.

And despite the cautionary tales that come up in the film, I’ve had a huge amount of fascinating social conversations with people because of my interest in simulation theory, and I imagine it’s true about a lot of people who spend a lot of time thinking about it. I don’t know if they all think about it alone, right? Or if it’s something that they enjoy talking about with other people.

If technology became sufficiently advanced, would you create a simulated world?

It’d be very tempting, especially if I could add the power of flight or something like that [laughs]. I think the biggest reason not to, and I just saw this on a comment on Twitter yesterday, and I don’t know if it had occurred to me, but what might stop me is all the responsibility I’d feel to all the people within it, right? If this were an accurate simulation of planet Earth, the amounts of suffering that occurs there for all the creatures and what they went through, that might be what stops me from doing it.

If you discovered you were living in a simulation, would it change the way you behave in the world?

I think I would need more information about what the nature of the purpose of the simulation is. If I found out that I was the only person in a very elaborate virtual-reality game, and I had forgotten who I really was, well then I would act very differently then I would if I learned this is an accurate simulation of 21st-century America as conceived by aliens or people in the far future, in which case I think things would stay more or less the same — you know, my closest personal relationships, and my responsibility to my family and friends.

Just that we’re in a simulation isn’t enough. If all we know is that it’s a simulation, kind of the weirdness is that that word “simulation” starts to mean less. Because whatever qualities the real world has and ours doesn’t is inconceivable to us. This is still as real as real gets.