Bitcoin is Trust

Last week, I invited a few friends to come together and talk about Bitcoin. The conversation was wide ranging (read: ill-organized), but interesting.

Three key topics emerged out of the djin:

Here is my summary of our discussion of each:

Past Examples

There are a lot of interesting analogous examples to bitcoin as a virtual store of value / currency. E-gold and m-pesa are examples of two digital currencies backed by tangible value – they are different than bitcoin, but offer interesting lessons.

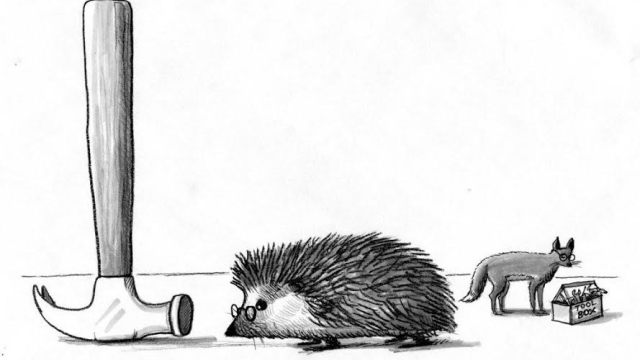

We explored two historical examples that map closely to how bitcoin is used: Rai Stones and Wampum. Rai Stones are very large limestone petrospheres used on the island of Yap as a form of trade currency. The importance of Rai Stones is that they are recognized by the entire culture as valuable and that transactions and ownership are public; because of this, actual physical ownership is unnecessary (a Rai Stone, irrevocably lost at sea, was even used in the abstract as valid currency).

Our discussion around Wampum offered another interesting lesson; that the value of something can reflect a recognition from both parties of the fact that it took lots of human effort to create.

Moving from Wampum back to the digital world, we discussed the example of virtual currency (Facebook Credits, Linden Dollars, QQ Coins, etc.). Each of these have been used as a store of value for a group. Some of these have even built large transaction volumes, but have been backed by a key central actor and are generally used only in the context of that actor’s primary service. That said, It’s worth noting that QQ Coins became so popular outside of QQ’s primary service, that it was banned for use buying physical goods and services in China. Bitcoin is being used in China today in similar ways, and much of its growth in value over the last 6 weeks has been in response to Chinese activity (and American speculation about Chinese activity).

So we’ve seen small communities, online and off, trust a new store of value. Creating systems in some cases that thrived for 1000+ years. An open question remains with bitcoin — can we establish that level of trust on a global scale with a diverse network of actors providing the credibility and liquidity?

So far bitcoin has done this, but there are some key challenges to keeping it legitimate with a number of diverse actors. You can see why, when asked to define bitcoin, the best response was “bitcoin is trust.”

Making BTC Legitimate

For it to be an actual currency, there is a need to “think in BTC first.” The volatility of BTC makes this really difficult. While A consultant may be willing to peg her consulting rate to BTC, it’s unlikely her clients will be interested in stomaching the current volatility of BTC as anything other than a favor to that consultant.

Even current examples of merchants accepting BTC today are usually not holding bitcoin. These merchants use an intermediary to price all transactions in BTC based on an up-to-date exchange rate with US Dollars (or Canadian Dollars, Euros, etc.). The merchant only rarely chooses to ever hold BTC, instead getting daily deposits in their preferred currency. For the average business, cash flow management trumps speculation.

Regardless of any structural issues it may or may not have (e.g. being a deflationary currency), bitcoin today is too volatile to be a legitimate currency. This volatility is encouraging new bitcoin owners and the maturation of an ecosystem around bitcoin. It may be preferable that during the “growth phase” the market is volatile and speculative, but bitcoin‘s value will have to stabilize before we can start to think of it as a legitimate currency.

If it legitimizes at all, bitcoin is likely to slowly become a robust currency in places where using it to transact is preferable to the pre-existing options (or where there are no pre-existing options). International transactions, online transactions, and unstable countries were brought up as potential proving grounds for bitcoin as a legitimate currency.

At some point, miners will make less mining new coins from the coinbase than they will from transaction fees. When this is true, all miners will have to standardize on charging some sort of fee. Market forces will drive consolidation of miners, which is a serious threat to the stability and viability of the bitcoin ecosystem. The system needs some competition between miners.

We may have to create additional incentives for miners. It’s possible transaction fees will cover this, but it’s also possible that other incentives could be thought of. We floated the idea of whether the aggregate compute power could be sold to be used for something else. Unfortunately, ASICs have very limited use and do the vast majority of mining. Primecoin is an alternative crypto-currency that offers a different way of submitting proof-of-work that is intrinsically valuable (and therefore could be used to additionally subsidize mining).

There was an entertaining suggested use for all the pooled compute resources of ASIC bitcoin miners: try to crack the security of wallets holding lots of BTC and steal their money. Impressively, someone in the group had already done the math on whether this was feasible — at the current global hashrate, it would take 2 million years to break the encryption of a wallet.

We didn’t dive deeply on alternative coins, other than to note that the people interested in these coins as vehicles of value creation are driven almost exclusively by speculation, not by belief that it will be a better currency, and that the markets are less liquid and far more volatile. Alt-coins are where the technical community tries new types of features and works out philosophical disagreements on how crypto-currencies work best.

What Does Bitcoin Allow You to Do?

Going back to our examples of Rai and Wampum from before, the most interesting aspect of each is that they served as both a currency and a way to encode key information – specifically being used as a record of critical events. Rai stones are used to mark social transactions (e.g. marriages, treaties and alliances) and Wampum belts are woven into patterns that represent ideas – allowing them to be used for keeping records, acknowledging treaties, and passing down stories to the next generation.

Bitcoin offers us the same ability to encode many types of financial transactions (experiments already exist to use the block chain to automate Notaries, DNS, and Stock Exchanges) and could easily be used for other types of trustable information storage.

At it’s core, bitcoin allows you to automate much of the infrastructure around financial transactions and cut out billions of dollars worth of unnecessary fees and middlemen. Automation is going to remove lots of humans from our global financial systems.

The financial services layer that gets built up around Bitcoin will be really interesting; to quote Naval Ravikant “any competent programmer has an API to cash, payments, escrow, wills, notaries, lotteries, dividends, micropayments, subscriptions, crowdfunding, and more.”

Jason noted that we are in the infancy of these services, but that over time new services will grow up to make dealing in bitcoin easier to understand and safer for the average citizen. A good early example of this is the Bitcoin Investment Trust which is basically SecondMarket trading expertise in procurement and safekeeping in return for a fee.

Aside from just automating human to human financial services, Bitcoin also enables us to create narrow-AI autonomous agents — basically, programs that offer some type of service that they are paid for in BTC, which the program uses to pay for it’s own costs. These programs could operate as autonomous businesses with no human oversight.

As an example of a type of business that could run this way, take a piece of ransomware called Cryptolocker, which encrypts critical files on your computer and requires that you to send them bitcoin to get the key to decrypt your files. This business could amass hundreds of millions of dollars worth of BTC without any additional human intervention (and in the near future, the program could actually be taught to clone itself and test new types of mutations in how it runs the business to optimize for profitability). Another example of this is the thought-experiment StorJ.

If you’re interested in this and like fiction, read Accelerando, which features sentient corporations as a key sub-plot, or Daemon which has a computer program that takes over hundreds of corporations and terrorizes the world.

The rest of these points didn’t fit into the themes above, but I thought were worth sharing:

Here was the reading list I sent around prior to the event (with a few new additions):