Your Science Could Soon Be Free, But Also Free of Skepticism

There’s good news and bad news about the openness of scientific information this week. The good news is that you might soon have access to more of it than ever. The bad news is that you might not know what to make of it.

First the good: a cadre of elite universities—Harvard, MIT, UC-Berkeley, Dartmouth, and Cornell—announced a commitment to expand the number of scholarly journal articles published open-access, free for anyone to read. Currently, nearly all of the top journals publish on a subscription basis. Universities pay those fees so their scientists have access to the latest research, but the information is closed off to the public unless you want to shell out a small fortune for them. Just accessing one Nature article as a non-subscriber will run you $32.

In their Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity, the five universities call for a new business model that would allow anyone to access these journal articles to follow the latest developments, double-check media reports about them, conduct their own research or whatever other reasons they might have. In the potential new model, universities would stop paying the subscription fees to access the journals and instead pay for the processing costs for the publication of research by their faculty. This way, journals would still cover their operating costs but the information could be open-access.

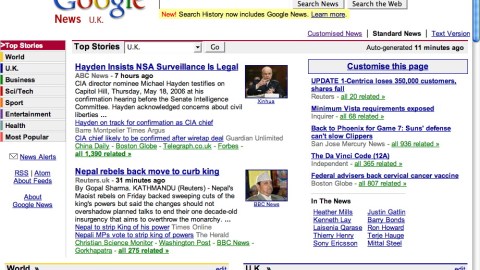

And then there’s the bad. Science journalism’s decline has featured some especially high-profile failures lately, like both CNN and the Boston Globe dropping their science sections. Universities have proposed their own solution to the receding amount of science in the mass media, but it’s one journalists aren’t going to like: colleges communicating directly to the public by putting their press releases in news feeders like Yahoo’s and Google’s.

Most press officers do a great job, and the quality and reliability of the information is quite good. But press releases are designed as promotional information for the university: they’re full of enthusiasm and devoid of skepticism about the research done by either asking hard questions of the scientists or talking to scientists not involved in the project. They lack context for the study that comes with comparing it to similar ones in the same vein, and other hallmarks of the work done by good science journalists.

Some information is better than none, it’s true. But a world driven by press releases as news is one where science is reduced to the level typically seen on sorry local TV broadcasts—single studies blown out of proportion, with no thought as to what it all actually means.