CJR on the Forthcoming Article: What’s Next for Science Communication?

Over at the Columbia Journalism Review, Curtis Brainard previews some of the major themes and proposed initiatives from a new co-authored paper I have appearing at the American Journal of Botany. The article is scheduled for the October issue as part of a special symposium on science education and communication. A pre-publication author proof is available with the final paper online later this month. If you have been following the recent blog debates over science communication but have been looking for more substantive sources, this paper is probably for you. It’s also a good introduction to the relevant research in the area.

From Brainard’s article at CJR:

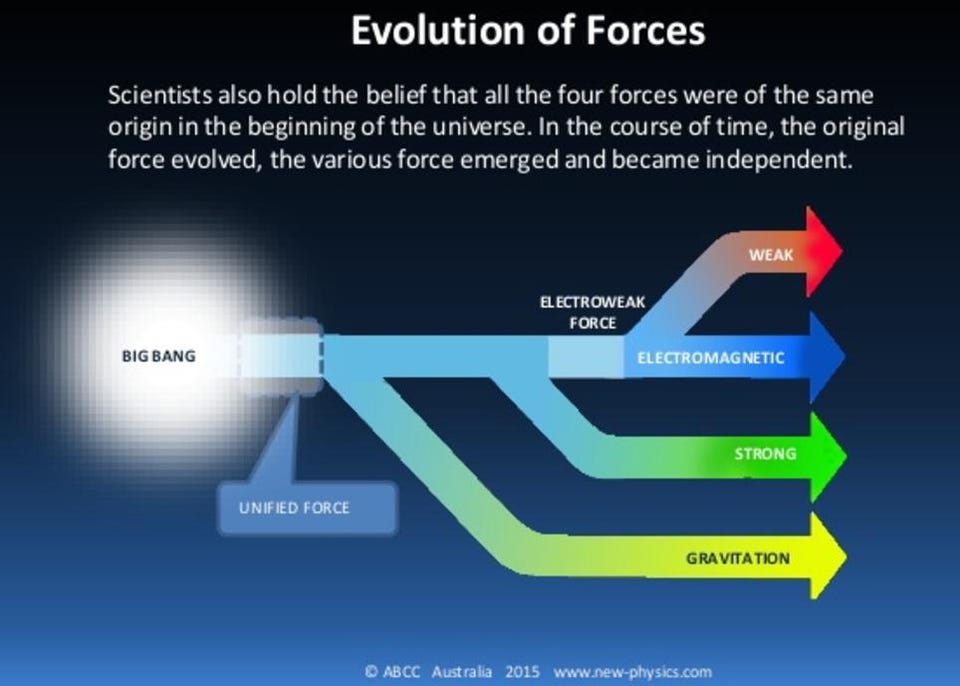

In an upcoming paper (pdf), science communications experts Matthew Nisbet and Dietram Scheufele argue that scientists must learn to better explain their research in ways that are relevant to different communities’ lives. Much like Hansen in his early years, scientists are wont to believe that the “facts will speak for themselves,” Nisbet and Scheufele argue. Thus, “when the relationship between science and society breaks down,” scientists often rush to blame public ignorance of science. In doing so, they ignore the “far stronger influences on opinion … such as ideology, partisanship, and religious identity.”

Nisbet and Scheufele acknowledge their critics, who have “argued that scientists should stick to research and let media relations officers and science writers worry about translating the implications of that research.” That would be the ideal situation in an ideal world, Nisbet and Scheufele concede. In reality, however, politicians and the public often seek scientists’ opinions on matters of policy and government–so scientists should know how to explain the import of their work and their knowledge effectively. They cannot, as Slouka put it, “keep to their reservation.”

Still, scientists must eschew anything that smacks of a “top-down persuasion campaign,” Nisbet and Scheufele warn. To “democratize science,” they must engage the public during the formative stages of research, so that the public doesn’t feel like anything is being foisted upon society. Nisbet and Scheufele advise using a variety of media platforms–blogs, online video, social media, new documentary genres, and storytelling techniques such as satire–to accomplish that goal. New forms of collaboration will also be necessary.

“Government agencies and private foundation should fund public television and radio organizations as community science information hubs,” they write. “These initiatives would partner with universities, museums, public libraries, and other local media outlets to share digital content that is interactive and user-focused.”

That might worry Slouka, who is leery of the sciences’ “symbiotic relationship with government, with industry, with our increasingly corporate institutions of higher learning.” Indeed, there is already some worry within the journalism community about groups like the National Science Foundation “underwriting” a variety of current media projects. A recent paper in Nature Biotechnology, on which Nisbet was co-author, acknowledged “the danger … of this type of public engagement emphasis becoming too conflated with marketing and public relations.”

In the upcoming paper, Nisbet and Scheufele make a point of reiterating that framing scientific communications in terms of people’s cultural, ideological, or religious concerns should never attempt to “sell” science to the public–only explain its relevance, good or bad. In fact, their call for a “more empirical understanding of how modern societies make sense of and participate in debates over science and merging technologies” resembles Slouka’s plea to “humanize” the educational systems. Gathering the data Nisbet and Scheufele are looking for would mean more work in the social scientists and humanities.