Why Predator Strikes In Pakistan Are A Bad Idea

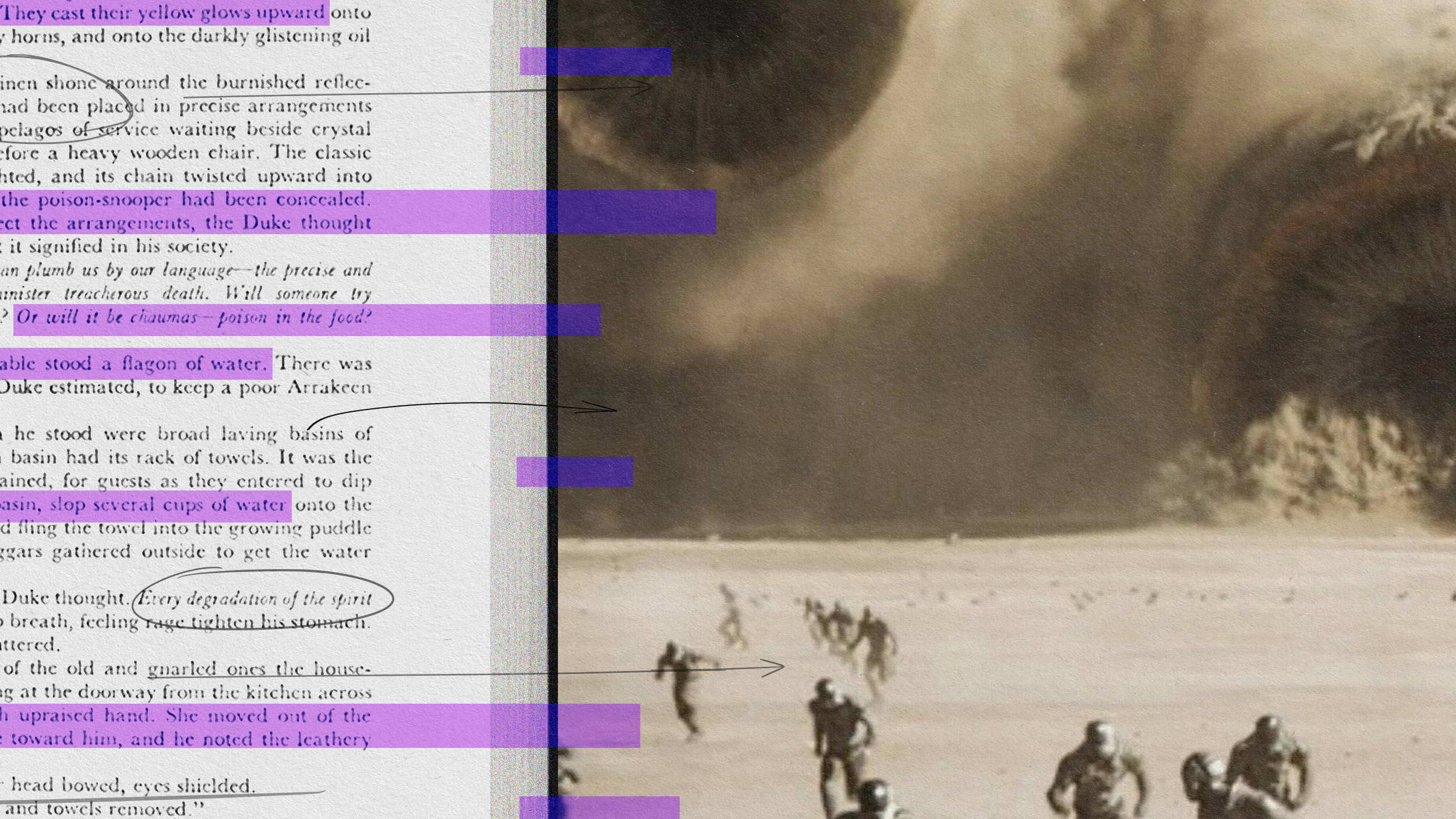

A burka is visible from 20,000 feet. So is an AK-47. That is not insignificant, as the debate rages on over whether to send more troops to Afghanistan. One alternative to putting thousands of more troops in harm’s way is flying more unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as Jane Mayer recounts in this week’s New Yorker, which have proven remarkably effective at killing terrorists. But is a pilotless drone the best response to extremists bent on attacking the United States?

The arguments in its favor are manifold. Slightly smaller than a Cessna, the $4 million aircraft—a drop in the bucket by defense standards—is able to hover for hours at a time while its “unblinking eye” tracks its targets. Fourteen out of 20 wanted al-Qaeda suspects have been killed by UAVs, including one of Osama bin Laden’s sons. The aircraft are so popular that our military is considering employing them more in places like Somalia and Yemen. Mexico is even said to be considering deploying them against its drug cartels.

Indeed, the number of targeted killings by UAVs has skyrocketed under Obama, who made waves in 2007 when he said he would unilaterally attack Pakistan if given actionable intelligence on al-Qaeda’s whereabouts. His critics pounced on him at the time, submitting this as proof he was a featherweight on foreign policy, yet many of them are now calling for a more muscular posture on Pakistan.

On the surface, UAV strikes make sense. The fewer the terrorists, the safer our troops are in the region. They disrupt terrorists’ training regimen, keep them off cell phones (too easy to trace), and create dissention and confusion within the ranks. Zeroing in on a camp of Taliban fighters seems to make more sense than blowing up Fidel Castro’s cigar.

Yet it is still a shortsighted tactic, not a long-term strategy. Any Hellfire missile that goes awry and kills civilians hands the Taliban a huge propaganda victory. The very fact that we use pilotless planes is held up by our enemies as evidence of America’s unwillingness to sustain casualties. That may explain why the number of propaganda tapes produced by al-Qaeda set record highs this year, after falling in 2008.

And the efficacy of these strikes, which rests on the notion that al-Qaeda’s leadership is irreplaceable, remains unclear. If we kill a dozen top lieutenants, a dozen more just rise up in their place. By killing civilians in the process—by most estimates, well over 600 non-combatants have been killed by these aircraft since 2006—we just create more al-Qaeda sympathizers, leaving us worse off than before. We often underestimate how deeply ingrained revenge is in the Pashtun tribal culture.

Not to mention the U.S. military’s rules of engagement are getting turned on their head. UAVs are becoming ever more autonomous, to the point where soon it may be a machine, not some pilot sitting in Nevada, which identifies and fires on targets. That raises difficult legal and ethical issues. If there is collateral damage, how do you court-martial a machine? Ron Arkin, a robotics engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology, is devising an “ethics code” for drones like the Reaper to understand rules of engagement (i.e. not to target hospitals or folks waving white flags). “When you take man out of the process, you lose your human discrimination that bears upon your ethics but also your effectiveness,” says Loren Thompson of the Lexington Institute.

Yet, there are scant signs the Obama administration will reverse course and halt these strikes. They make for great headlines back home, allowing the White House to come off as tough on terrorism, even as it lacks a long-term strategy to rid South Asia of its terrorist safe havens. But whenever we look for a simple technological fix to something as complex as terrorism, there are bound to be snags.

If tallying higher Taliban body counts is our end goal, then we should be talking about a surge of UAVs to the region. But if we want to eradicate the conditions that make extremism fester and win over the sympathies of local Pashtuns, it is hard to believe that a pilotless drone flying at 20,000 feet can accomplish anything.