Is Art History Better Unsaid Than Red?

A new tour at the Museum of Modern Art in New York has many seeing red over “seeing” Reds in the collection. As reported in Art News, Artist Yevgeniy Fiks’ “performative tour” titled simply enough “Communist Tour of MoMA” begins with the current exhibition Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art before spilling messily into the political leanings of other artists throughout the collection. Although the Soviet Union disappeared from maps and globes and Communism is presumed dead, Fiks’ digging up of old political skeletons (some buried more shallowly than others) raises the question of whether any value can come from such politicized art history. Is art history better unsaid than Red?

According to his website, Fiks claims that his work “is a reaction to the collective amnesia within the post-Soviet space over the last decade, on the one hand, and the repression of the histories of the American Left in the US, on the other.” Working in that grove, Fiks tries to “discover[]and reflect[]on repressed micro-historical narratives that highlight the complex relationships between social histories of the West and Russia in the 20th century.” Many of those “micro-historical narratives” appear in modern art, which become silent testimonials to the Communist past lurking amongst us still today.

Before the Cold War, before McCarthyism, before Khrushchevbanging his shoe at the U.N. while braying about burying people, and even before Gorbachev’s Glasnost, Communism in America could actually be discussed without total disdain. For those who looked for greater racial and economic equality in America between the two world wars, Communism (at least in the ideal sense rather than in actual practice in Russia) offered hope. Intellectuals could attend meetings in the 1920s and 1930s to talk about racism or poverty in a way that mainstream American politics rarely did. Years later, the label of card-carrying Communist (aka, “Pinko” or “Red”) stuck to many who pursued racial or economic improvement in America and not a total overhaul of the system. Even into the 1960s, African-American Civil Rights leaders such as the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. could have FBI file compiled on them for suspicion of “Communist leanings.”

Many of the artists on Fiks’ “Communist tour of the MoMA” fit a similar profile of intellectual curious in social change but not necessarily the communist “way,” i.e., the Russian model. Diego Rivera, however, did much more than just flirt intellectually with Communism. Perhaps more than any other major artist of his time, Rivera traveled among major players in the movement both in Mexico and Russia. His wife, the then relatively unknown artist Frida Kahlo, even had an affair with Leon Trotsky when the exiled Communist leader fled to Mexico for sanctuary and lived with the artist couple. Like most of Rivera’s relationships with women, however, his bond with Communism was messy, fiercely passionate, and ultimately a failure. Fiks brings in other artists such as Jackson Pollock (who attended communist meetings in the 1920s and studied with Rivera’s compatriot and fellow Communist muralist, David Alfaro Siqueiros), Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Rene Magritte, and others.

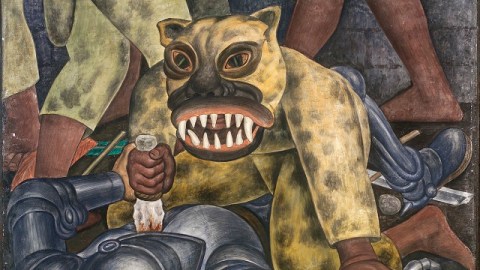

But does any of this politicized art history further our understanding or appreciation of the art or artists? Can we “see” the Communism in their art? When we look at Rivera’s mural Indian Warrior (shown above), are we simply looking into the face of the furious proletariat rising up against the prone bourgeoisie? Or is the politics of even such a political man secondary to the art? Can this kind of history be extended to other political philosophies? Can we look at a still life by Giorgio Morandi and determine what he liked in the 1920s (and later disliked in the 1930s and 1940s) about Italian Fascism? An “Anti-Semite’s Tour of the MoMA” would feature Degas, Cezanne, and a slew of Dreyfuss Affair era French artists—but to what end? Do Degas’ dancers dance with bigotry in their hearts (or feet)? I think that Fiks’ tour and ideas have some value in recovering elements of history, but I think he dances on dangerous ground when he tries to find the politics (especially still-emotionally charged politics such as Communism) in the paint.

[Image:Diego Rivera.Indian Warrior. 1931. Fresco on reinforced cement in a metal framework, 41 x 52 ½” (104.14 x 133.35 cm). Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts. Purchased with the Winthrop Hillyer Fund SC 1934:8-1. © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, New York for providing me with the image above from the exhibition Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art, which runs through May 14, 2012.]