In this wide-ranging talk, controversial professor Bret Weinstein covers several topics: politics, technology, and tribalism, just to name a few. But ultimately the former Biology professor at Evergreen College talks with us about why this particular decade is so interesting. Given the explosive growth of the 20th century, he argues that we’ve come to the end of that particular boom and have just started searching frantically to keep the pace that we’ve come to expect. When that change doesn’t come, Weinstein posits that we search for scapegoats, turn inwards, and start to attack ourselves. And that’s paraphrasing just some of the half-hour talk we have for you.

Bret Weinstein: We’re heading into a very dangerous phase of history; human beings being addicted to growth are constantly looking for sources, so when we feel austerity coming on we tend to become more tribal.

Unfortunately a perfectly free market will not allow benevolent firms to survive in the long run.

My argument is not an argument for centrism. I regard utopianism as probably the worst idea that human beings have ever had.

We find ourselves unfortunately stuck in an archaic argument about policy; frankly the left and right are both out of answers and they should team up on the basis that they agree at a values level about what a functional society should ideally look like.

—

Human beings, like all creatures, are the product of adaptive evolution, but they are highly unusual amongst evolved creatures. In order to understand them it is very important to recognize certain things that make us different from even the most similar creatures, like chimpanzees. The most important difference is something I call the omega principal. The omega principal specifies the relationship between human culture and the human genome.

The most important thing to realize about human beings is that a tremendous amount of what we are is not housed in our genomes; it’s housed in a cultural layer that is passed on outside of genes.

Culture is vastly more flexible, more plastic, and more quickly evolving in an adaptive sense than genes, which is why in fact cultural evolution came about in human beings.

It allows human beings to switch what they are doing and how they are doing it much more quickly than they could if all information that was adapting was stored in DNA.

One of the very important benefits of understanding this relationship between the genome and the cultural attributes of human beings is that it frees us to engage in an analysis of the evolutionary meaning of behaviors without having to know where exactly the information is stored.

This is especially important with complex phenomenon, which may be partially housed in the genome and partially housed in the cultural layer—something like human language, for example.

Human language as a capacity is obviously genetically encoded, but individual human languages are not.

And so if we are to talk about the adaptive utility of human language, being obligated to specify what is housed where could put off that discussion for generations, whereas if we recognize that the cultural aspects of language—as well as the genomic aspects of language—are all serving a united interest then we can begin to understand the meaning of something like language in rigorous, adaptive terms.

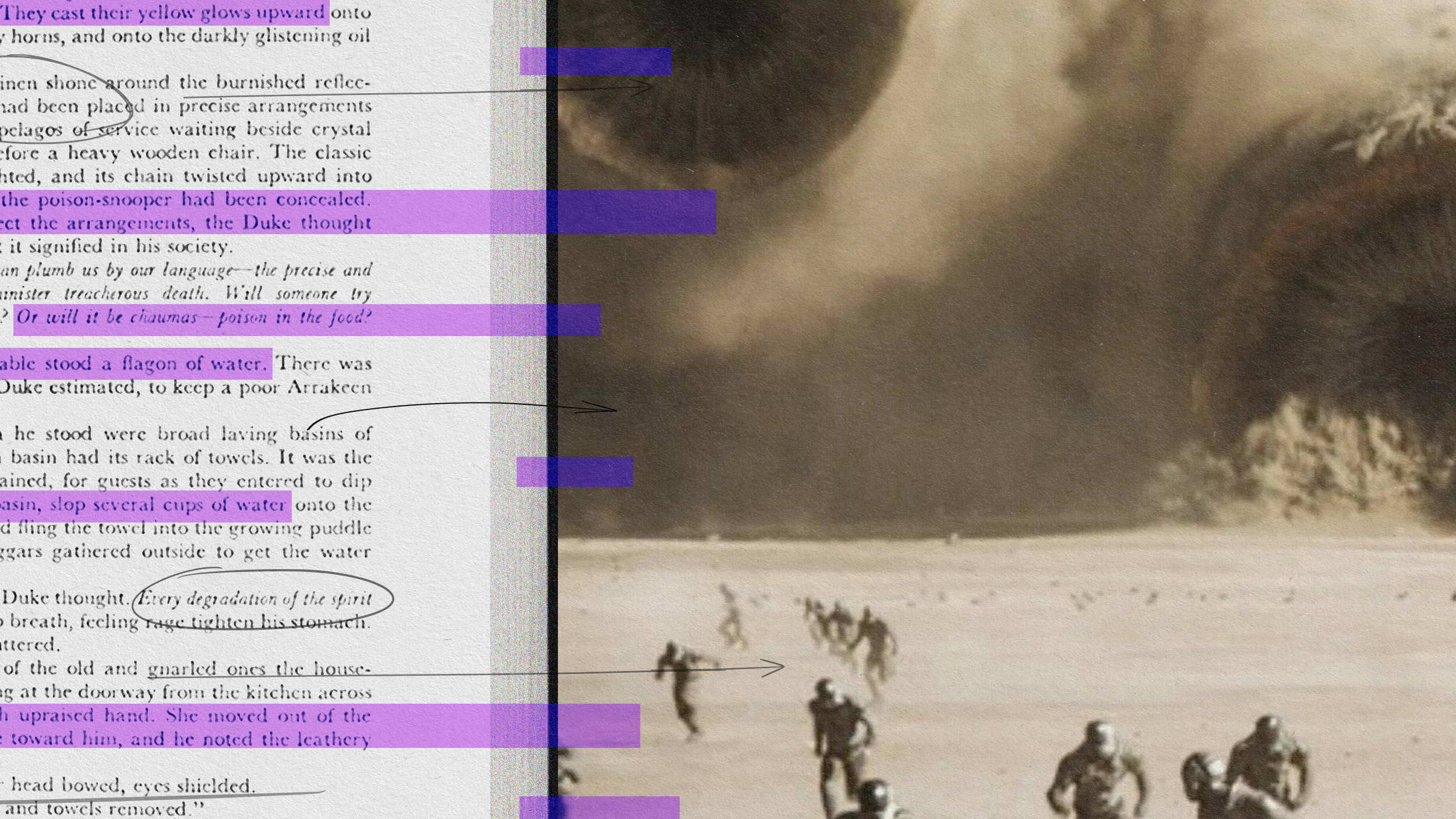

The hypothesis of cultural evolution, which has now has been sufficiently tested to be regarded as a theory—of human cultural evolution, is the invention of Richard Dawkins, who in 1976 in The Selfish Gene coined the term ‘meme’ as an analog for gene; it’s a unit of cultural evolution.

The genome creates a brain that is capable of being infused with culture after an individual person is born.

If culture was evolving to do things that were not in the genome’s interest they would effectively be wasting the time and resources that the genetic individual has access to on frivolous things at best. So the genome would shut down frivolous culture were it a very common commodity. So the theory of memes tells us that there is a process, very much like the one that shapes our genomes, at work in the cultural layer.

That does not mean, however, that the cultural evolving layer is free of obligation to the genome. In fact, the cultural layer is downstream, and one of the things that we have repeatedly gotten wrong is we have attempted to just simply extend the rules of adaptive evolution as we have learned them from other creatures and apply them to human beings, and it leads to some unfortunate misunderstandings.

The fact that we are primarily culturally informed tells us that culture serves the genetic interests almost all of the time.

Which is to say, if you look at a long-standing cultural trait, it doesn’t matter what it is—whether it’s music or religion or humor—all of those things must be paying for themselves in terms of genetic fitness.

Once we’ve recognized that, we can skip to the much more interesting question of: “in what way do some of the remarkable cultural structures that we see serve genetic interests?”

Some of them seem absolutely paradoxical if we try to imagine that they are serving our genomes, and yet that is the conclusion that we have to reach when we realize that the genome is not only tolerating the existence of that culture, but it is facilitating its acquisition.

This suggests a very odd state of affairs for human beings, in which we have minds that are programmed by culture and that can be completely at odds with our genomes.

And it leads to misunderstandings of evolution, like the idea that religious belief is a mind virus—that effectively these belief structures are parasitizing human beings, and they are wasting the time and effort that those human beings are spending on that endeavor, rather than the more reasonable interpretation, which is that these belief systems have flourished because they have facilitated the interests of the creatures involved.

Our belief systems are built around evolutionary success and they certainly contain human benevolence—which is appropriate to phases of history when there is abundance and people can afford to be good to each other.

The problem is, if you have grown up in a period in which abundance has been the standard state you don’t anticipate the way people change in the face of austerity.

And so what we are currently seeing is messages—that we have all agreed are unacceptable—reemerging, because the signals that we have reached the end of the boom times, those signals are everywhere and so people are triggered to move into a phase that they don’t even know that they have.

Despite the fact that human beings think that they have escaped the evolutionary paradigm, they’ve done nothing of the kind; And so, we should expect the belief systems that people hold to mirror the evolutionary interests that people have rather than to match our best instincts.

When we are capable of being good to each other because there’s abundance, we have those instincts; and so it’s not incorrect to say that human beings are capable of being marvelous creatures and being quite ethical.

Now I would argue there’s a simple way of reconciling the correct understanding—that religious belief often describes “truths” that in many cases fly in the face of what we can understand scientifically—with the idea that these beliefs are adaptive.

I call it the state of being literally false and metaphorically true. A belief is literally false and metaphorically true if it is not factual, but if behaving as if it were factual results in an enhancement of one’s fitness.

To take an example: if one behaves in, let’s say, the Christian tradition, in such a way as to gain access to heaven, one will not actually find themselves at the pearly gates being welcomed in, but one does tend to place their descendants in a good position with respect to the community that those of descendants continue to live in.

So if we were to think evolutionarily, the person who is behaving so as to get into heaven has genetic interests. Those genetic interests are represented in the narrow sense by their immediate descendants and close relatives; in the larger sense they may be represented by the entire population of people from whom that individual came, and by acting so as to get into heaven the fitness of that person, the number of copies of those genes that continue to flourish in the aftermath of that person’s death will go up.

So the believe in heaven is literally false—there is no such place—but it is metaphorically true in the sense that it results in an increase in fitness.

If you think about all of the things that you know human beings to have done over the course of human history you’ll realize that humans must have shifted from one niche to the other again and again.

Effectively humans are a niche-switching creature.

That is the human niche—to discover new things to do when the ancestral ways have petered out and are no longer useful.

Innovating new ways to be is very much the human toolkit. When human beings adopt an opportunity, their population grows in proportion to the size of that opportunity, and that opportunity essentially should be thought of as a frontier.

Now, there are many kinds of frontiers that humans have discovered. The most obvious kind of frontier is a geographic frontier: when a population discoverers an uninhabited island—or in an extreme case they discover a continent that has no people on it—that is a tremendous opportunity, and a tiny population can grow to gigantic size given such a bit of good fortune.

But there are less-obvious kinds of frontier as well.

A technological frontier occurs when people discover a mechanism for doing more with the territory that they have.

So for example, if you think about a piece of territory that has been inhabited by hunter-gatherers, at the point that farming is either invented or brought in (discovered by some other population that same piece of territory), if it is hospitable to farming, can support a much larger population. So it functions just like having discovered a new landmass, because the size of the population that exists on the current landmass goes up as a result of the fact that the land is made more productive.

There’s a third kind of a frontier, which I call a “transfer” frontier, which is not really the same in the sense that it is zero sum: somebody has to lose in order for somebody else to win.

But from the point of view of an individual population, another population that cannot defend the resources that it has is an opportunity, and so many of the worst chapters in human history involve one population targeting another population that can’t defend the resources that it owns.

And so for the population doing the targeting, capturing those resources functions like having discovered a new landmass or a new technology that allows productivity to go up.

All of these types of frontiers eventually run out. There is simply a limit to the number of geographical locations that can be inhabited. There may always be a next technology, but the discovery of new technologies comes in fits and starts, and there can be long dry periods where you have reached or exceeded the limits of a technological opportunity and the next one is nowhere on the horizon.

So human beings, being addicted to growth, are constantly looking for sources.

And when geographic frontiers and technological frontiers don’t provide those opportunities, human beings will sometimes look within their own population and figure out who can’t defend the resources that they hold and they manufacture reasons that they are not entitled to keep them.

And so when we feel austerity coming on we tend to become more tribal.

And this is a very dangerous pattern of history, for example, what took place during the Holocaust when the German population decided to target European Jews, and it made up reasons that those Jews were not entitled to continue.

So, what we are effectively seeing in the present is a circumstance in which we have reached the end of a boom, and human beings are becoming tribal because that is the natural transition at the end of a growth period, and we are naturally inspired to look for something to replace the growth that has run out.

This is why many of these abhorrent messages have become resonant in the present to many people. They are waiting to hear somebody explain what population isn’t capable of defending its resources and to explain what justification will be used to pursue those resources—and to transfer them.

Many people are optimistic that technological breakthroughs will continue to provide access to growth.

And this is an unfortunate perspective, because it leads us into a false sense of security, not realizing that—being evolutionary creatures—we are not programmed to preserve that state of growth and make it last a long time.

What we are wired to do is to capture the benefits of them and bring them into use.

What that means for most creatures is: when a non-zero sum opportunity has been discovered, creatures create many more like themselves; basically more mouths to feed.

For modern people, sometimes creating more mouths is not the natural reaction, but creating greater consumption is.

And so as much as we are wired in a way that is beneficial—where we discover new ways of doing more with less that provides abundance—we are also wired to use up that abundance in consumption.

And in fact we have a dynamic in which our economic theories—the ones that we run society on the basis of—actually define economic health. Growth is the conversion of useful energy into useless heat and the conversion of useful materials into useless waste. So we have what I call a throughput society where we view ourselves as doing something right as we are taking resources that might be made to last a long time and we use them up.

So, for example, if I were to invent a microwave oven that is just as useful as the one you have but would last ten times as long as the one you have, intuitively it seems that that should be a very good thing; but from the point of view of the economy it will result in a reduction in growth because fewer microwave ovens will be sold.

So by defining our economic terms such that they lead us to “correct” for improvements in efficiency and cause us to capture resources and use them up in one kind of consumption or another, we set ourselves up for a situation in which no matter how good an opportunity we discover it is inherently temporary.

Ethics evolved to limit the self-destructive behavior internal to a population.

Unfortunately in our present circumstance, where we have handed over so many functions to an anonymous marketplace, people that learn where the ethical landscape (that we describe to ourselves), where on that “landscape” there are opportunities that are unpoliced—actually come out ahead.

If you discover things that are unethical that therefore many people will not engage in, but you’re willing to engage in those things and there’s no penalty—either informal or legal—built in the system, then you will come out ahead as a result of your increased freedom because you’re not ethically limited to the narrower set of acceptable behaviors.

And so unfortunately society has begun rewarding people who are good at figuring out where we are not policing our ethical standards and exploiting those opportunities as a competitive advantage.

The fate of benevolent firms in the market is a very important topic. Unfortunately a perfectly free market will not allow benevolent firms to survive in the long run.

Now that may seem like an overly declarative statement, but the problem is this: if you imagine two firms, one of which is perfectly amoral and will do absolutely anything that generates a profit and the other one, which is constrained by ethical beliefs that prevent it from availing itself of certain economic opportunities, then it doesn’t matter what the economic circumstance is: the amoral corporation or firm always has an advantage.

The best that can be true is that the ethical choice is also the strategically best choice and the two will be dead even, but in any case where there’s any distinction whatsoever between the ethical choice and the perfectly amoral choice, the amoral firm has the advantage of being perfectly free to avail itself of opportunities that its competitor cannot reach. And what this does is it causes evolution of firms in the direction of ruthlessness.

It is often times the case that people who set things in motion in the marketplace with the best of intentions are surprised at what ultimately becomes of their innovations.

Google famously began with the prime directive “don’t be evil” and many people have recognized that over time Google has become more ruthless than it was at the start. This is actually a perfectly predictable phenomenon.

The reason that Google was able to have noble objectives at first was that it existed in an immature market where having ethical restraints on what is possible did not put it at a competitive disadvantage to any viable competitor that it faced.

As a market matures, its tolerance for firms that restrain themselves is much reduced, and a perfectly efficient market has effectively no tolerance for self-restraint. And as a result of this, firms evolve to become more ruthless or they parish.

And either way what we find is an increased tendency in a market—as it becomes more efficient—towards ruthlessness.

This does not have to be the case, but it is the result of the fact that we leave the market free for this kind of evolutionary trajectory.

If we were wise about this we would realize that a free market is not the ideal state.

We don’t want to tinker, we don’t want to meddle in a way that is overly disruptive of innovation, but we do want to tinker enough that the evolutionary tendency produces the kinds of firms that we wish to see rather than ones that behave in a way that horrifies us.

We find ourselves unfortunately stuck in an archaic argument about policy where right and left disagree about the wisdom of tinkering with society to make certain things better.

In general the left is overly enthusiastic about meddling and it doesn’t appreciate the full danger of unintended consequences, and the right is overly skeptical of the advantages of tinkering and prone to focus on the unintended consequences, and be underambitious with respect to making society better.

But the entire argument is based on ideas of the 18th and 19th century, and those ideas are simply not up to date enough to deal with the problems of the 21st century.

So my argument would be that those on the left and right who are in favor of liberty as perhaps the highest human value should put aside their policy differences—because frankly the left and right are both out of answers—and they should team up on the basis that they agree at a values level about what a functional society should ideally look like.

And we should actually begin a new conversation about policy in which we investigate what we can do that the founders of this nation (and others that are modeled on it) couldn’t imagine because they didn’t have the tools at their disposal.

In particular, we should be very careful that whatever solution-making we engage in is evolutionarily aware.

The founders of the United States did not, of course, know anything about evolution.

Those who have constructed our markets did not know anything about evolution.

And what they have done repeatedly is accidentally set up an evolutionary system in which adaptation begins to take place without anybody’s awareness.

And what that tends to do is it tends to take the best intentions of those who set up these systems and overrun them with things that simply function.

It results in dangerous patterns like regulatory capture, where those entities that figure out how to tinker those parts of the governance apparatus that are supposed to regulate them come out ahead of those that don’t attempt to tinker with those elements.

My argument is not an argument for centrism. I believe that the answers we are looking for are not actually on the map of possibilities that we are familiar with. We are effectively living in Flatland, and what we have to do is learn to detect the Z axis so that we can seek solutions of a type that will at first, be unfamiliar to us.

There’s a great danger in doing this, of course, which is Utopianism. I regard Utopianism as probably the worst idea that human beings have ever had, and if anyone doubts that that’s the case you should look at the history of Utopian ideas across the 20th century. The untold number of bodies that stacked up as a result of Utopian ideas run amok is absolutely staggering.

Utopians make two errors: the first error is they prioritize a single value.

Now, because of the way mechanisms function, anytime you optimize a single value you create incredibly large costs for every other value in question.

By prioritizing things like liberty or equality, if you do so in a narrowly focused way you can’t help but generate a dystopian result, because all of the other values that people might hold are effectively destroyed in the process.

The other mistake that utopians make is they tend to imagine that they know what the future state should look like and they miss what every inventor knows, which is that your grandest ideas are crude to begin with. You have to build a prototype in order to figure out what you don’t understand.

And so I would argue we cannot describe the future that we should be seeking.

We can say what direction it probably is in and we can head in that direction intelligently, but the minute we start telling ourselves that we know what the state that we are trying to construct looks like we will suffer the same failure that an inventor that wanted to bypass the prototyping stage would suffer.

There are two kinds of conflict that people can find themselves in: they can be in conflict when they have fundamentally different interests from each other, but very frequently for human beings we will find ourselves in conflict with somebody with whom we are aligned but we have a difference of opinion about what to pursue or in what manner to do so.

And there are a couple of things that evolution can tell us about how to address such a conflict to be productive.

The first thing is it is very important to figure out what it is that causes you to disagree. Sometimes you may be disagreeing over values. So for example, if the two people prioritize things differently they may have a different sense about what should be done.

On the other hand, people may be disagreeing about how to accomplish something while being completely aligned with respect to what it is that is desired.

So establishing what it is that has you disagreeing is very important. I’ll give you an example.

I frequently find, as somebody who comes from the political left, that I have very easy conversations with Libertarians on the right, and those conversations remain easy until we get to the question of policy.

At the point that we get to the question of policy we diverge. And the reason that we diverge is actually that we have different expectations about the danger of creating new policy, but we do not disagree over the values.

A right-of-center economic Libertarian will agree that ideally the market works best when opportunity is as broadly distributed as possible, so that everybody has an opportunity to innovate. They may disagree about how equal the opportunity is currently, and they may also disagree about the wisdom of attempting to redistribute opportunities so that people who don’t have it can gain access to it, but there’s no disagreement over whether it is a desirable characteristic.

On the other hand, there may be disagreements over what objectives are worthy of pursuing; that some people would like to see liberty prioritized over equality, for example, and some other group of people may want to see equality promoted at a cost to liberty—those are both valid perspectives and it is worth understanding that when values are at issue there may actually be no resolution. Two reasonable people can disagree over how valuable various objectives are, and when that’s the case simply recognizing that the difference cannot be resolved at the level of discovering that somebody is correct and somebody is incorrect because in fact both positions are equally valid.

I would say that there is a failure in the way we view argument, that in general I think our politicized and polarized atmosphere has caused us to look at arguments as always tactical.

And one thing that you find when you interact with people who are very adept intellectually is that they are often capable of putting aside suspicion about the motives of the people with whom they are arguing, and they will argue not to win but to discover what is true.

And it’s a very different state of affairs, because although nobody likes being shown to be wrong the great thing about being shown to be wrong is that it gives you the opportunity to correct your understanding and to be wiser the next time you encounter the question, rather than entrenching yourself in a wrong position and suffering the costs of being wrong every time you encounter the question.

So, putting aside a desire to win and substituting a desire to discover what is true is the key to discovering truth through argument, which benefits everybody who participates; those who have turned out to be correct, those who have turned out to be incorrect and in general what typically happens is one will discover that nobody was perfectly correct, and then all sides have increased their understanding based on hashing out the details of what they disagree over.

We’re heading into a very dangerous phase of history where a large number of people, especially young people, have become convinced that the free exchange of ideas is not only no longer necessary but is actually counterproductive; and so they set out to silence those who have opinions at odds with theirs.

Some of the people who have opinions at odds with theirs truly believe abhorrent things, but the problem is: until you fully understand a topic, you don’t know which opinions to shut out.

One has to actually engage beliefs that are at odds with your own beliefs in order to figure out whether what you believe is correct, and to improve where it isn’t correct.

So shutting down speech has become the mode for a large number of individuals who believe they see very clearly what is wrong with civilization and what must be done to improve it—and they are unfortunately shutting down people who have vital things to tell them that they definitely need to know.