These maps show how much range America’s wild animals have lost

In Feral, his book proposing a re-wilding of our natural environment, George Monbiot refers to Shifting Baseline Syndrome as a major cause in our misperception of what is ‘natural’.

As individuals, we lack a multi-generational perspective. Our environment is in its ‘natural’ state when we are young, or so we assume. The only environmental destruction we really notice is what occurs within our own lifetimes.

Humanity’s baseline for what is natural keeps shifting with every new generation, clouding our view on longer processes of environmental damage and degradation.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome can have perverse effects on our attempts at nature conservation – sometimes, we conserve the environmental destruction, rather than restoring the environment to its previous natural state.

Monbiot has a particular bone to pick with the sheep that are used to maintain large tracts of Britain in a near-desert condition. Those sheep are an invasive species, he argues, and the medieval switch to a wool-based economy destroyed the richly biodiverse forests that covered most of the island.

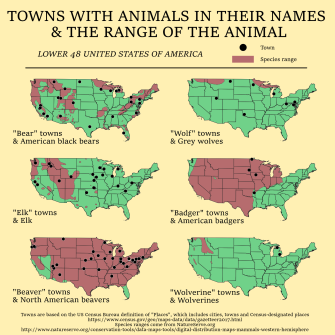

America too is subject to the paradox of ecological degradation: its scope is so massive that it’s hard for us as individuals to notice. These maps suggest some interesting markers to get a sense of the discrepancy between our ‘natural environment’, and that of previous generations.

They compare the geographic spread of cities and towns (1) in America named after native animals and the current geographic distribution of those species. As you may have expected, most indicate a huge reduction in the range of said animals.

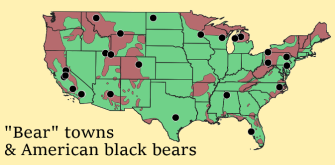

Let’s start with bears: as the map indicates, they roam far and wide: from the Appalachians all the way into Maine, on the coasts of Virginia, in Florida, along the Mississippi in Louisiana, in Arkansas and Missouri, throughout the west and the Pacific states. Most ‘bear’ towns align more or less with the animal’s current range:

- Bear Valley and Bear Valley Spring, Big Bear City (2) and Big Bear Lake (all in California),

- Bear River in Wyoming and Bear River City in Utah;

- White Bear Lake in Minnesota, Upper Bear Creek in Colorado and Bear Creek Village in Pennsylvania;

- Bear Rocks also in Pennsylvania and Bear Dance in Montana;

- Bear Flat in Arizona and Bear Grass in North Carolina;

- Three places called Bear Lake (two in Michigan (3) and one in Pennsylvania);

- and four towns all called Bear Creek (in Montana, Wisconsin, Florida and California).

But some indicate that the majestic predator once had an even wider distribution:

- two towns also called Bear Creek, in Texas and Alabama;

- Four Bears Village in North Dakota;

- and a town simply called Bear, in Delaware.

It’s worse for wolves: they’re limited to two relatively small areas near the Canadian border, far away from most ‘wolf’ towns:

- Two towns called Wolf Lake, one in Minnesota, the other in Michigan;

- Wolf Point, Montana (4) and Wolf Creek, Utah;

- Lone Wolf, Oklahoma (5) and Wolfdale, Pennsylvania;

- Wolf Summit, West Virginia and Wolf Trap, Virginia.

Judging by the places named after the animal, elk used to be prevalent across most of the country. ‘Elk’ towns are concentrated in the Midwest:

- Elk Run Heights and Elk Horn, both in Iowa (6);

- Elk Point in South Dakota and Elk Creek in Nebraska;

- Elk River in Minnesota and Elk Mound in Wisconsin;

- Elk City and Elk Falls, close to each other in Kansas; and another Elk City in Oklahoma.

Some elk towns are further east:

- Elk Rapids in Michigan, Elk Grove Village (7) in Illinois and Elk Creek in Kentucky;

- Banner Elk (8), North Carolina and Elk Garden, West Virginia.

The current range is limited mainly to the Rockies and the Pacific Northwest, with small scattered patches elsewhere. Some elk towns actually in elk country:

- Elk Creek and Elk Grove, both in California;

- Elk City and Elk River, both in Idaho;

- Elk Plain in Washington and Elk Ridge in Utah and Elk Mountain (9) in Wyoming.

Badgers are holding firm in most of the country, absent only from the eastern third of the country (and a small part of the northwest). There are still badgers in all badger towns on this map:

- Three towns simply called ‘Badger’ (in Minnesota, South Dakota and Iowa);

- and one called Badger Lee, Oklahoma.

Beavers are everywhere, except in California, Nevada and Florida. And so are beaver towns, with concentrations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Nevada and Oregon.

- Seven towns are just called ‘Beaver’ (in Arkansas, Iowa, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah and West Virginia);

- Six towns called ‘Beaver Creek’ (two in Ohio, one each in Oregon, Maryland, Minnesota and Montana);

- Five towns called ‘Beaver Dam’ (in Arizona, Kentucky, Ohio, Nevada and Wisconsin);

- Three towns called ‘Beaverton’ (in Alabama, Michigan and Oregon) and two called ‘Beaverdale (in Iowa and Pennsylvania);

- And then there’s Beaver Valley in Arizona, Beaverville in Illinois, Beaver City and Beaver Crossing in Nebraska, Beaver Bay in Minnesota and Beaver Dam Lake in New York, and Beaver Falls and Beaver Springs in Pennsylvania (10).

Poor wolverines: clinging on to a dwindling strip of land in the northwest, with small colonies remaining in California and on the Nevada-Utah border. Where are the times when they roamed Michigan in such numbers that two towns in that state – Wolverine Lake, near Detroit, and Wolverine, near the top of the state’s Lower Peninsula – were named after them?

Map found here at Data is Beautiful on Reddit.

Strange Maps #931

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

(1) The dots represent populated places, i.e. cities, towns or census-designated places as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. The maps do not include other topographical features named after said animals (e.g. Wolverine, an unincorporated community in Kentucky, Wolverine Canyon in Utah, Wolverine Creek in Kansas, or Wolverine Hill and the Wolverine Mine, both in Michigan). Species ranges come from natureserve.org.

(2) Big Bear City is the location of a quartz dome that is worshipped as the Eye of God by the Serrano, a tribe native to the area.

(3) One township in Kalkaska County, the other in Manistee County.

(4) A city in the Fort Peck Indian Reservation and the home of the annual Wild Horse Stampede, “the Grandaddy of Montana Rodeos”.

(5) Named after a Kiowa chief rather than the animal.

(6) But not Elkader, named after Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine, a 19th-century Algerian fighter against French colonialism.

(7) Despite being surrounded by a largely industrial area and its proximity to O’Hare International Airport, Elk Grove Village is home to a small herd of elk – indeed kept in a grove. The herd was brought to the area in the 1920s and is maintained by the Chicago Zoological Society. Unrelatedly, Elk Grove Village also is the hometown of Billy Corgan and James Iha, both of the band Smashing Pumpkins.

(8) By the early 19th century, elk had disappeared from the area. The National Park Service has now reintroduced small numbers of elk to western North Carolina.

(9) The setting of Elk Mountain, a graphic novel about the relationship between superheroes and the communities they defend.

(10) That’s not counting the names of half a dozen other places in Pennsylvania, including Big Beaver and New Beaver.