DERECHO-NOIA!!!!!!

Derecho Alert!!!!!! AAAIIIGGGHHH!!!! Grab the kids! Run for the basement, quick!

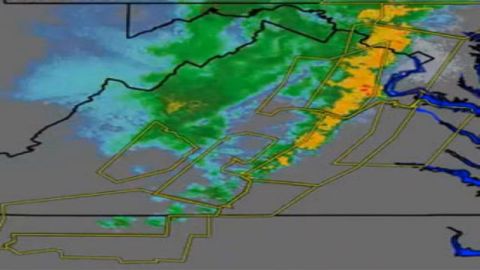

As this is being written a line of severe thunderstorms is sweeping across sections of the Northeast (and heading for my house). There has already been a possible tornado near Elmira New York, tornado warnings have been posted for many areas and, tornadoes or not, the damage from this weather will be severe in some places, even life threatening. But this is hardly the first time such weather has raked this part of the country. Why the especially dire warnings, all day, this time?

It’s a spot lesson in human cognition and risk perception. What used to be ‘a line of dangerous thunderstorms’ is now popularly known as a derecho, a word familiar only to meteorologists until a severe line of dangerous thunderstorms smashed through the Baltimore-Washington area in June, killing 12 and leaving more than a million people without power for days. Suddenly this dangerous but familiar sort of weather has a new name, and (sorry Mr. Frost) ‘that has made all the difference’. (Mark Memmott of NPR gives us the background on the word derecho here.)

The very fact that the word has leapt into the lexicon has changed really dangerous weather into REALLY DANGEROUS WEATHER. The fear is greater because the risk is new. Not meteorologically of course, but semantically, and that’s enough to do the trick. New risks are scarier to us than risks we’ve lived with, even dangerous ones. New risks are unfamiliar. Unfamiliarity means we are uncertain…that we don’t have a library of experience to help us put the threat in perspective. Uncertainty makes us feel powerless because we don’t know what we need to know to protect ourselves. And powerlessness…lack of control…makes any risk scarier.

There is another unique aspect to human cognition at play in this DERECHONOIA. The brain uses a mental short cut called ‘availability’ to quickly, subconsciously gauge how much weight to give something. When a sight or smell or sound or fact comes in that suggests danger, the quicker anything comes to mind that we already know about that danger, the more the brain knows to pay attention because memories of threatening situations are usually encoded more powerfully, and come to mind faster. So the more readily available something is to our consciousness, the more the brain responds by giving it extra attention.

The Ring of Fire derecho of June 29 (amazing video of it sweeping across the country from Iowa to the east coast) is fresh in the minds of many of the people facing this storm. That alone makes the alert ring louder than a forecast of ‘a dangerous line of thunderstorms’. On top of which the whole idea of this violent kind of weather is…at least semantically…new. So it’s scarier than the very same sort of weather when it has struck in the past.

This is neither good nor bad, right nor wrong. It’s just a terrific demonstration of how subjective we are about gauging risk and danger…and a cautionary example of how what makes us more afraid or less afraid isn’t just the risk itself, but also how it feels. That sort of risk perception is prone to error, sometimes producing judgments and behaviors that feel right but fly in the face of the evidence, and actually raise our risk, something I call The Perception Gap.

By the time you read this the storm will probably have passed, hopefully with minimal damage. But here are two questions for those of you who are/were at risk; did you do things to prepare…monitor the weather, have a place you could seek shelter, prepare for the loss of electricity, etc.? Great. Did you take the same steps the last time there was a severe thunderstorm watch, even though it wasn’t called a derecho. Perhaps not. (Me neither!) Oops.