The Dangers of Corporate Democracy

“We may have democracy,” Justice Louis Brandeis once said, “or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” Justice Brandeis thought that eventually the people who controlled the wealth of the country would come to control the country itself. One way or another, the rich would buy political influence, as happened in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union. A democracy would for all practical purposes become an oligarchy.

Over the last thirty years wealth in the U.S. has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few. Since the beginning of the Reagan administration, the real income of the richest 1% of the population more than doubled, while the real income of the average American has been essentially stagnant. For the all the talk about what people generally think of as “welfare”—public programs to support the poor—the widening gap between the rich and the rest of us is in part the consequence of corporate subsidies and tax cuts that largely benefited the rich. This transfer of money was supposed to “trickle down” to average Americans. But for the most part the money just stayed in the hands of the already wealthy.

Now the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (pdf) to let corporations buy political ads gives financial interests even greater influence over our political system. During the presidential primaries in 2008 a activist group called Citizens United produced a documentary attacking Hillary Clinton. Because Citizens United was partly funded by corporate donations, it wasn’t allowed under a provision of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law to pay a cable operator to make its video available. Rather than ruling narrowly on the technical legal questions, the Supreme Court chose to overrule two of its old decisions—even calling a hundred year-old precedent into question—to find that not allowing corporations to buy political ads is an unconstitutional infringement of their right to free speech.

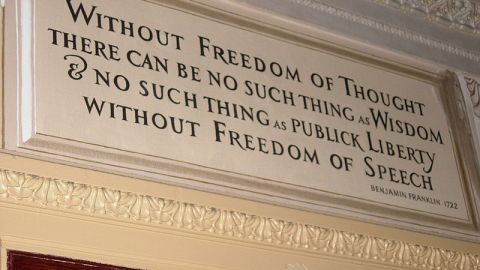

It is certainly not obvious that freedom of speech necessarily entails an unlimited freedom to spend money to broadcast your words. Nor is it clear that institutions should have the same rights as individual people to spread their message. Indeed, as Kris Broughton recently wrote, a Maryland public relations firm recently announced its intention to run for Congress as a way of showing the absurdity of the doctrine that corporations had the same legal rights as people. And whatever one thinks of the legal issues, it is striking that the Roberts court has upheld laws abridging individuals’ right to actually speak, while expanding corporations’ rights to express themselves more generally. Still, the court was certainly right to argue that it’s hard to draw a bright line between permissible avenues of expression and impermissible ones.

In any case, the consequences of the decision may be difficult to live with. It’s not that it will largely benefits Republicans, who by and large represent the interests of corporations and very wealthy. The more fundamental problem is that corporations are already able to field armies of lobbyists to push Congress into writing the regulations for their own industry, often helping themselves to huge handouts of taxpayer money along the way. As President Obama said in the State of the Union, the court’s decision threatens to “open the floodgates for special interests.” While most Americans agree with the Supreme Court that political spending is a form of free speech, Gallup found that most also favor limiting the amount of money that people or corporations can give. In one way or another, we need to find a constitutional way of doing just that. Because while it is important to protect everyone’s right to express themselves, it is also important to make sure that no one can buy our democracy.