When Maps Stare Back: IJsseloog and Makian

I always go for the window seat on airplanes. I say always. To be honest, only recently did it dawn on me: It looks like a map down there! And then, on a recent flight over the Netherlands, I found the map staring back at me. I blinked first.

Airplane windows are designed to let light in, not to let you look out. Unless you’re a tiny ten-year-old, you need to crouch to get a peek through your tiny, awkwardly placed porthole. Looking through the multi-layered plexiglass, often obscured by dirt and frost, is as frustrating as peering through a broken kaleidoscope.

And even if daylight and weather permit, there’s often little to keep the eye entertained. On a transatlantic trip, weather and flight pattern permitting, the interminable ocean will be punctuated by a sighting of Kap Farvel, the southern tip of Greenland.

Shorter trips are more interesting: more likely to pass over rivers and coastlines, cities and islands. Spotting something out of your window that you’ve only seen in an atlas before is as thrilling to airborne mapheads as bumping into a movie star on the street must be for other celebrity spotters. Look: Flamborough Head! There: Cape Cod! Oh Em Gee: that has to be Tehran!

About half an hour into a flight from Brussels to Stockholm, the SAS plane was cruising over Flevoland, the Dutch province reclaimed from the IJsselmeer. The outline of the two rectangles dredged up from the seabed was obvious enough.

From an altitude of about 30,000 feet, the landscape was a small-scale map of the Netherlands, with very little detail visible. I failed to distinguish Urk, the ancient island of fishermen absorbed into the Northern Flevoland polder. But the strict geometry of agriculture on the man-made land was obvious and reminiscent of the American Midwest.

Something weird in the water (Image: Frank Jacobs)

Then I felt watched. In the corner of the window, to the southeast of where Urk was supposed to be, an island was staring up at me. A perfect circle, fringed by an asymmetrical earthen enclosure, it looked a bit like an eye. Or a Millennium Falcon.

What could it be? Not an atoll, for this is the wrong latitude for coral. Nor is Holland’s muddy geology right for a sinkhole like the Great Blue Hole off Belize, let alone wave-breaking volcano craters like Alaska’s Kasatochi Island.

Kasatochi Island (NOAA image in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The island’s perfect circularity and its man-made surroundings – the IJsselmeer is the dammed-up, domesticated descendant of the previously wily and lethal Zuiderzee – point to an artificial origin. But what was its purpose? Giving reverse planespotters like me the eye can hardly have been the point.

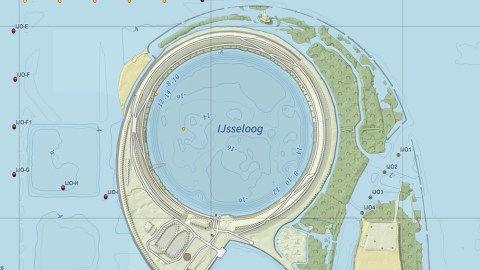

The island is appropriately called IJsseloog, ‘Eye of the IJssel’, after the main river debouching into the Ketelmeer, the narrow bay between Northern and Southern Flevoland where the island is located.

The river is the reason the island is there. In the decades since the closure of the Zuiderzee in 1932 and the drainage of Flevoland, the IJssel’s silt deposits had been building up in the Ketelmeer, threatening to clog up the area’s waterways.

IJsseloog (image courtesy of Jan-Willem van Aalst, via Wikimedia Commons)

Dredging away the silt to maintain a depth of 3.5 m for the channels to the IJssel proved relatively easy. But depositing the silt somewhere was another matter altogether: it was polluted with metals like zinc and quicksilver and could not yet be treated. Hence IJsseloog – basically a giant garbage chute for the Ketelmeer.

IJsseloog was started in 1996 and finished in 1999. At the centre of the island is a circular pit with a depth of about 150 feet (45 m) and about 3,280 feet (1 km) across, ring-fenced by a 10-foot (3-m) dyke. The reservoir can hold up to 880 million cubic feet (20 million cubic metres) of silt, with one third of that capacity reserved for silt from beyond the Ketelmeer. Leakage into the Ketelmeer is prevented by keeping IJsseloog’s water below the level of the Ketelmeer (which on average is less than 10 feet deep).

From 1999 to 2002, the Ketelmeer east of the island was cleaned up, while the area immediately west of the island was cleaned from 2010 to 2012. Research is presently underway to determine whether the further west part of the Ketelmeer, east of the Ketelbrug bridge, needs to be cleaned as well.

Remediation of the deposits proceeded by decantation at a port facility, from where the cleaned silt will then be used for IJsselmonding, a new ecological area yet to be constructed. When only dirty sludge is left, the impermeable bowl of an island will be sealed with clay and sand, and the island will be given over to recreation.

IJsseloog is one of many artificial islands in in Dutch rivers and estuaries, the most famous one probably being Neeltje Jans, which was built to facilitate construction of the Easter Scheldt Dam, and the one with the coolest name being De Dode Hond (originally called Daphnium, but renamed after the dead dog buried there).

‘t Eyland Makjan, geheel Bergagtig, by Jacob van der Schley (1750). (Image in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Researching IJsseloog, I came across another perforated island connected to the Netherlands – at least historically. The island of Makian in Indonesia (formerly the Dutch East Indies) is represented on this map as a mountainous Möbius strip around a giant donut hole. Weirdly, the map does not correspond to the reality at all: Makian is a volcanic island, yes, but the crater is not a giant lake, rather a relatively small caldera on an entirely mountainous island, as indicated on the map (“Geheel Bergagtig“).

Maybe the cartographer wanted to emphasise the island’s volcanic nature. Or perhaps the interior is so inhospitable that he chose to focus on the villages and forts on the coast.

Perhaps one day, from my window seat, I’ll be able to check that for myself…

Strange Maps #684

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].