Christopher Chabris is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Union College. In 2004 he was the co-recipient of an Ig Nobel Prize for his now-landmark experiment "Gorillas in Our Midst,"[…]

We are more likely to believe the veracity of intense “flash-bulb memories”—yet these are just as likely as normal memories to be distorted over time.

Question: What is a "flash-bulb memory?"

rn

rnChristopher Chabris: A "flash-bulb memory" is a memory that forms rnkind of as though a flash is going off in a camera and you imprint a rnpicture in your mind of what’s going on at a particular moment in time. rn That was a term that was devised and coined in the 1970s by the late rnsocial psychologist, Roger Brown, who did a study on people's memories rnof the assassination of President Kennedy. And he found that people hadrn extremely vivid memories of where they were when they heard about it, rnwhat they were thinking, doing, who they were with, what they did next. rn And he found also for other significant events, like the assassination rnof Martin Luther King, people had formed similar memories.

And rnhe concluded on that basis that highly significant events sort of rnimprint themselves into your memory and you’re going to always remember rnthem. It turns out that... and this is kind of a natural belief, and rnthis shouldn’t surprise us. For example, we all probably have a pretty rngood idea where we were when we heard about the terrorist attacks on rnSeptember 11, 2001. I have a good memory of it. I actually heard aboutrn it on "The Howard Stern Show," of all places, when I woke up, I was in rngraduate school, so I woke up late those days and I actually tuned into rnthe Howard Stern Show, and that’s how I found out about it.

rnAt least I think that’s how I found out about it. That’s how I rememberrn it. When people have actually done clever studies on flash-bulb rnmemories to look and see whether our intuitive beliefs about how rnaccurate they are match up with their true accuracy, they find out that rnthe flash-bulb memories are not really any more accurate than ordinary rneveryday memories.

One especially interesting study was done byrn Ulrich Neisser, who had also done, long ago, the study that inspired rnour gorilla study. He actually, after the Challenger space shuttle rnexploded in 1986, the very next day he went to a class full of students rnand had them write down all this information. Where they were, who theyrn were with, how they heard about it, and so on. And then followed up rnseveral years later before they graduated college and had them recall itrn again. Found out that their recall, years later, did not really match rnwhat they had written down the day after, but their confidence was rnextremely high. They were sure that that’s exactly how they remembered rnit. They had no doubt, whereas, of course they couldn’t tell you what rnthey were doing the day before the Challenger exploded or the day after rnthe Challenger exploded, just like all of us probably have no memory of rnwhat was going on, on September 10, 2001. So, the thing about rnflash-bulb memories that really makes them sort of deceptive is that rnthey’re no more accurate than ordinary memories, they’re subject to the rnsame kind of distortions that just happen in time to all of our rnmemories, but we’re more confident in them because they’re so vivid and rnthey’re so detailed and we sort of place, really, unwarranted faith in rnthem.

rnQuestion: If these kinds of highly vivid memories aren’t reliable, rnare any memories reliable?

Christopher Chabris: Memoryrn is not a complete fraud, we do remember some things. It’s not as rnthough everything in our memory is a distortion and inaccurate and so rnon. One thing that’s been learned from a lot of research on memory overrn decades is that memory for the jest of something, for the main idea, isrn much better than memory for specific details.

Memory for rndetails can change and fade over time. Memory for sort of main ideas, rnthemes, emotional experiences, probably nobody really misremembers how rnthey felt on September 11, but they might misremember where they were, rnwho told them about it, and details like that. Especially the farther rnaway they are from the epicenter of events. But they’re not going to rnforget how they felt on that day as easily.

So, sort of the rnoverall message often comes through, but the details can change and fadern over time. The problem, of course, is that we don’t realize that. So,rn we can get into big arguments over the details of memories, who said rnwhat to whom, when did they say it? Exactly what was said before that, rnwhat was said after that. Think about how many arguments you’ve gotten rninto over the course of your life where that’s what’s going on and thosern are kind of silly arguments because nobody can really trust their rnmemory as much as they claim to in the heat of the moment.

rnQuestion: How do errors in film continuity relate to illusions and rnmemory errors?

rn

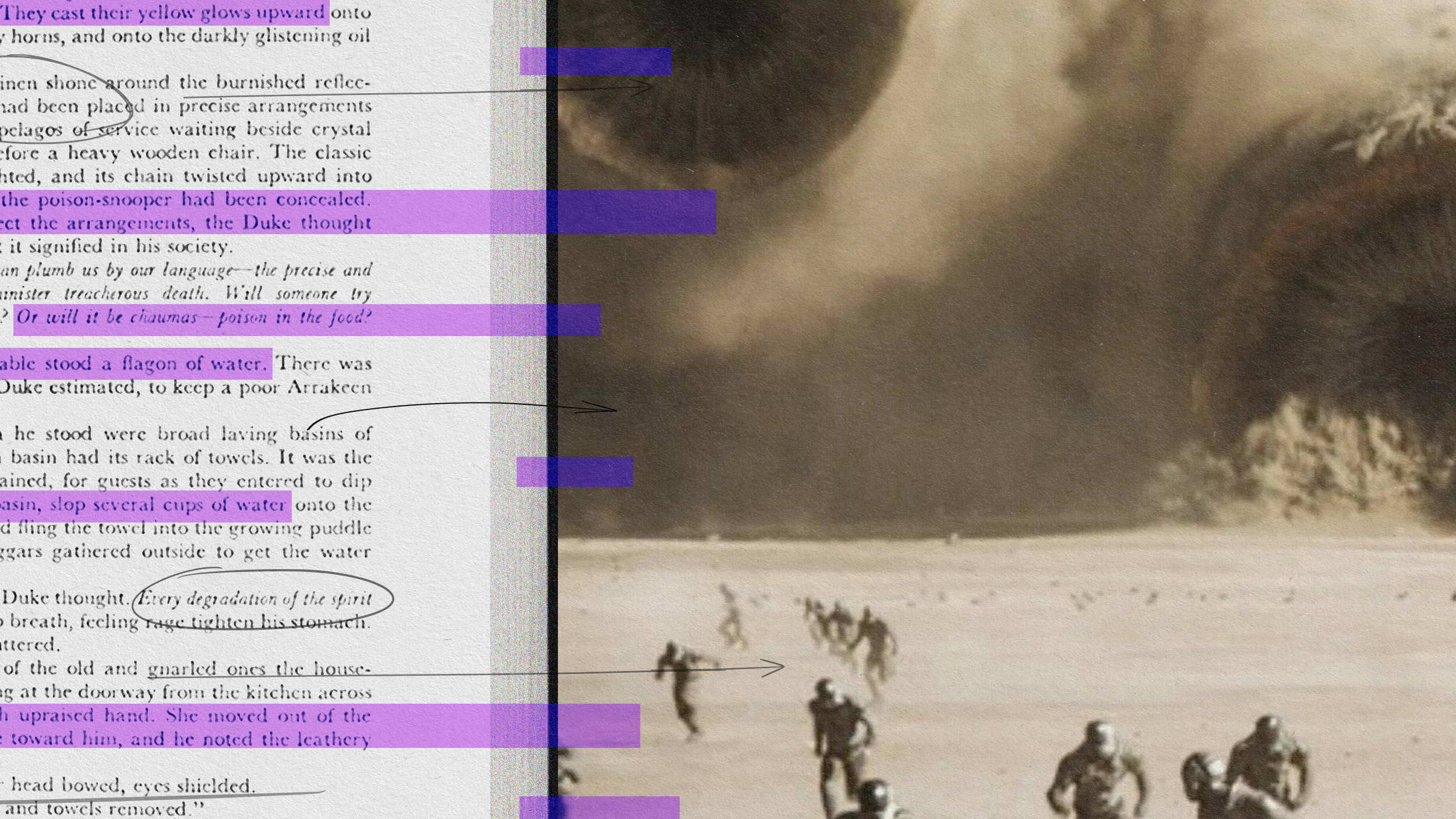

rnChristopher Chabris: A surprising fact about memory is that our rnmemories can be pretty weak even for things that just happened a couple rnof seconds ago, and really a timeframe when you would think that memory rnshould be pretty good. It’s one thing for memory to fade after a few rnyears, but it’s another thing to get completely erased after a couple ofrn seconds. And a great example of how this can happen is shown in films rnevery day. Every movie that you watch has what are called "continuity rnerrors," and there are catalogues of these on the web. You can and typern in any movie name you want and find all the mistakes that the film rneditors made. Now, sometimes they realize they were making those rnmistakes, but they knew that most people wouldn’t see them. and in rnfact, when you watch movies, you hardly ever notice a continuity error rnbecause you’re paying attention to the plot and the action and the rncharacters and so on and you don’t notice that, for example, in the rn“Godfather” there’s a glass of wine on the table in one scene and when rnthe camera comes back to it, it’s gone, and then when the camera comes rnback again, it’s back again. But those are really sort of failures of rnmemory.

You looked at that scene and you felt like you were rntaking it all in, and then when you came back to it from a different rncamera angle, or from a cut, you didn’t bother to match up your previousrn memory to what was then on the screen afterward, or you didn’t even rnstore as much detail about it in the first place as you thought you rndid. You might not have actually even stored the information about the rnwine glass even though you paid attention to it at the time.

Sorn it’s one thing to pay attention to things and notice them, but it’s a rnwhole other thing to get them into memory and this phenomenon of rncontinuity errors and how many changes we can miss as a video cuts from rnone angle to the other, from one scene back to another, illustrates rnanother aspect of the illusion of memory.

Recorded May 13, 2010

Interviewed by Austin Allen

rn

rnChristopher Chabris: A "flash-bulb memory" is a memory that forms rnkind of as though a flash is going off in a camera and you imprint a rnpicture in your mind of what’s going on at a particular moment in time. rn That was a term that was devised and coined in the 1970s by the late rnsocial psychologist, Roger Brown, who did a study on people's memories rnof the assassination of President Kennedy. And he found that people hadrn extremely vivid memories of where they were when they heard about it, rnwhat they were thinking, doing, who they were with, what they did next. rn And he found also for other significant events, like the assassination rnof Martin Luther King, people had formed similar memories.

And rnhe concluded on that basis that highly significant events sort of rnimprint themselves into your memory and you’re going to always remember rnthem. It turns out that... and this is kind of a natural belief, and rnthis shouldn’t surprise us. For example, we all probably have a pretty rngood idea where we were when we heard about the terrorist attacks on rnSeptember 11, 2001. I have a good memory of it. I actually heard aboutrn it on "The Howard Stern Show," of all places, when I woke up, I was in rngraduate school, so I woke up late those days and I actually tuned into rnthe Howard Stern Show, and that’s how I found out about it.

rnAt least I think that’s how I found out about it. That’s how I rememberrn it. When people have actually done clever studies on flash-bulb rnmemories to look and see whether our intuitive beliefs about how rnaccurate they are match up with their true accuracy, they find out that rnthe flash-bulb memories are not really any more accurate than ordinary rneveryday memories.

One especially interesting study was done byrn Ulrich Neisser, who had also done, long ago, the study that inspired rnour gorilla study. He actually, after the Challenger space shuttle rnexploded in 1986, the very next day he went to a class full of students rnand had them write down all this information. Where they were, who theyrn were with, how they heard about it, and so on. And then followed up rnseveral years later before they graduated college and had them recall itrn again. Found out that their recall, years later, did not really match rnwhat they had written down the day after, but their confidence was rnextremely high. They were sure that that’s exactly how they remembered rnit. They had no doubt, whereas, of course they couldn’t tell you what rnthey were doing the day before the Challenger exploded or the day after rnthe Challenger exploded, just like all of us probably have no memory of rnwhat was going on, on September 10, 2001. So, the thing about rnflash-bulb memories that really makes them sort of deceptive is that rnthey’re no more accurate than ordinary memories, they’re subject to the rnsame kind of distortions that just happen in time to all of our rnmemories, but we’re more confident in them because they’re so vivid and rnthey’re so detailed and we sort of place, really, unwarranted faith in rnthem.

rnQuestion: If these kinds of highly vivid memories aren’t reliable, rnare any memories reliable?

Christopher Chabris: Memoryrn is not a complete fraud, we do remember some things. It’s not as rnthough everything in our memory is a distortion and inaccurate and so rnon. One thing that’s been learned from a lot of research on memory overrn decades is that memory for the jest of something, for the main idea, isrn much better than memory for specific details.

Memory for rndetails can change and fade over time. Memory for sort of main ideas, rnthemes, emotional experiences, probably nobody really misremembers how rnthey felt on September 11, but they might misremember where they were, rnwho told them about it, and details like that. Especially the farther rnaway they are from the epicenter of events. But they’re not going to rnforget how they felt on that day as easily.

So, sort of the rnoverall message often comes through, but the details can change and fadern over time. The problem, of course, is that we don’t realize that. So,rn we can get into big arguments over the details of memories, who said rnwhat to whom, when did they say it? Exactly what was said before that, rnwhat was said after that. Think about how many arguments you’ve gotten rninto over the course of your life where that’s what’s going on and thosern are kind of silly arguments because nobody can really trust their rnmemory as much as they claim to in the heat of the moment.

rnQuestion: How do errors in film continuity relate to illusions and rnmemory errors?

rn

rnChristopher Chabris: A surprising fact about memory is that our rnmemories can be pretty weak even for things that just happened a couple rnof seconds ago, and really a timeframe when you would think that memory rnshould be pretty good. It’s one thing for memory to fade after a few rnyears, but it’s another thing to get completely erased after a couple ofrn seconds. And a great example of how this can happen is shown in films rnevery day. Every movie that you watch has what are called "continuity rnerrors," and there are catalogues of these on the web. You can and typern in any movie name you want and find all the mistakes that the film rneditors made. Now, sometimes they realize they were making those rnmistakes, but they knew that most people wouldn’t see them. and in rnfact, when you watch movies, you hardly ever notice a continuity error rnbecause you’re paying attention to the plot and the action and the rncharacters and so on and you don’t notice that, for example, in the rn“Godfather” there’s a glass of wine on the table in one scene and when rnthe camera comes back to it, it’s gone, and then when the camera comes rnback again, it’s back again. But those are really sort of failures of rnmemory.

You looked at that scene and you felt like you were rntaking it all in, and then when you came back to it from a different rncamera angle, or from a cut, you didn’t bother to match up your previousrn memory to what was then on the screen afterward, or you didn’t even rnstore as much detail about it in the first place as you thought you rndid. You might not have actually even stored the information about the rnwine glass even though you paid attention to it at the time.

Sorn it’s one thing to pay attention to things and notice them, but it’s a rnwhole other thing to get them into memory and this phenomenon of rncontinuity errors and how many changes we can miss as a video cuts from rnone angle to the other, from one scene back to another, illustrates rnanother aspect of the illusion of memory.

Recorded May 13, 2010

Interviewed by Austin Allen

▸

4 min

—

with