Forget fancy pens: in his early career, the award-winning cartoonist used sharpened dowels from the local meat market.

Question: What materials do you use as a cartoonist?

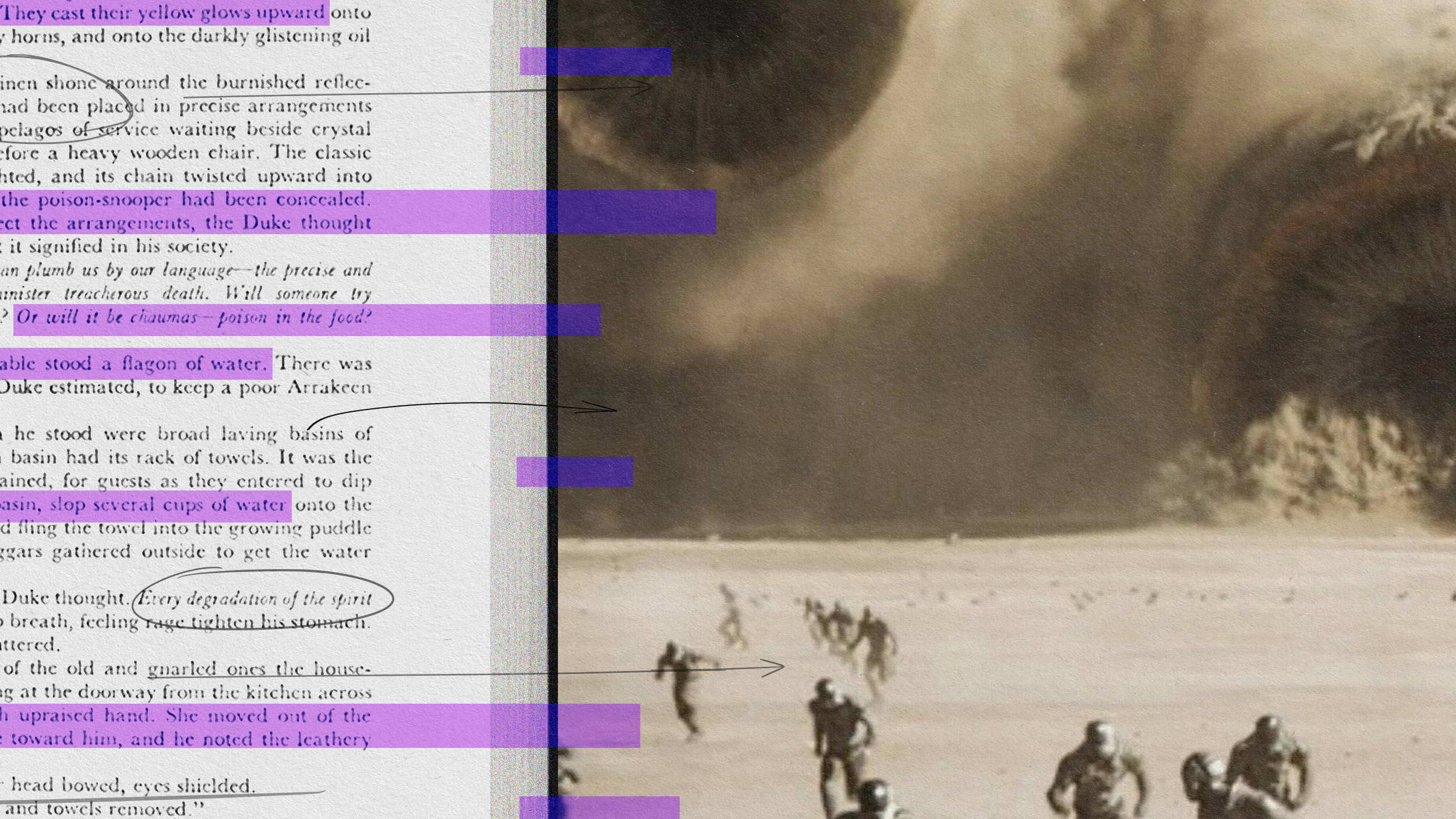

Jules Feiffer: Well it’s fluctuated over the years. And it’s changed a lot when I switched from the comic strip to doing ****. It’s a whole new way of working that I’ve never tried before and it was great fun to try and play with an experiment. But in the beginning, when I was at The Voice, I had a writing style down pat and I knew what I wanted to say, I just didn’t like the way it looked in print and so I fiddled around week after week, and if you see in the book Backing into Forward, the memoir, It shows the first four or five cartoons, all of which are done in different styles because I was floundering, and it took more than a month before I could settle on a line, the way I wanted it to look. And the way I came about that is, I had picked up some – I was living alone, I was a bachelor, and I picked up some meat from the meat market, and they had these round little dowels sticking in the steak with a pointed tip. And I thought, I wonder what that would be like if I dipped it in some ink. So, after I had my steak, I dipped it in some ink and I got a line that was both dry and in full character and quality and far better than any pen line that I was able to put on paper.

So, I went out and bought a bunch of these wooden dowels, these pointed wooden dowels and I began drawing with them. And I must have used that as my style, as my tool of choice for, I don’t know 10 years or so, and it got to be terribly laborious and slow moving because it’s not meant to be a pen. And finally I got fed up with that and switched to pen and ink, and never liked that very much and also, over the years, all I was trying to do in the artwork as it appeared in the paper, whether in The Voice, or in Playboy, or in syndication; and syndication just took The voice cartoons and ran them around the country. But all I wanted was a sense of immediacy. A sense of spontaneity. And I realized that the more I penciled and then inked over it the spontaneity always had a **** thick, and so I began drawing straight on the paper without any penciling. And by that time, photocopy machines were in, so I could just do them on any kind of paper, any size. Reduce them or fiddle with them and then cut them out and put them in a layout. And this took two or three times as long a penciling to get – and to do them over and over again. But I had finally a line that just jumped and that was vivid and alive and basically I was looking for a line, not a professional line, but more of an amateurs line that had life and vitality to it. And I was beginning to get that by not doing any predrawing.

So, from that day to this, and for more than 30 years I would think by now, that’s the way I’ve been working. And with the kid’s books, I layout this art on separate sheets of paper just to figure out what the final drawing would look like, and with that layout as a guide, I began the finished art and if it doesn’t work out well on this watercolor paper I’m drawing on, I tear it up and go on and go on and sometimes I do it three or four or five times before it works. And sometimes it comes out right the first time.

And then there’s the excitement of adding color, which I didn’t know anything about until 1997 or so, when I did my first picture book. So, the kid’s book in particular have been exciting for me because it forced me to go back to the work I loved as a young boy reading Sunday’s supplements and comics in the Sunday papers when I was six, seven, eight, nine. And number of which have been in wonderful collections, beautifully reproduced. And when I am working a book, I go through my library and take a look through some of the great cartoonists of the past, like Cliff Sterrett, who did “Polly and Her Pals,” or Winsor McCay who did “A Little Nemo in Slumberland,” and Herriman – and I just looked through these guys and looked for somebody to steal. You know, looked for who I could swipe, or turn into – who’s work I will turn into my work. And I still use, after all these years, these artists as inspirations.

So, here in my eighties, I go back to when I was eight for my inspiration.

Recorded on February 22, 2010

Interviewed by Austin rnAllen