Does the Brain Control the Mind or the Mind Control the Brain?

One of the first things students debate in a high school AP history class is Thomas Carlyle’s “Great Man” theory of history, taking sides on the bedeviling question: “Does the man make the moment or the moment make the man?” Carlyle led other 19th century historians in claiming, “The history of the world is but the biography of great men.” A similar orthodoxy long dominated neuropsychology: the brain controls the mind, which has no independent existence outside of the chemical reactions and patterns which constantly fire inside our brains. Neuro-biologists have long held that the brain exclusively drives the mind, and that the mind serves only the individual self.

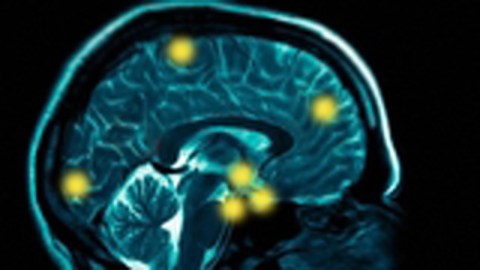

But a new breed of medical scientists is challenging this linear approach to the relationship between the objective physical world and subjective mental life. Dan Siegel, a professor at UCLA medical school, argues that the mind can be shared with others, and that these inter-personal neural networks can in fact shape the brain. The brain and the mind obviously have an intimate relationship, but the mind is different: it is a collection of thoughts, patterns, perceptions, beliefs, memories and attitudes. As Siegel explains, “The mind can use the brain to perceive itself, and the mind can be used to change the brain.”

Siegel is author of the best-selling Mindsight and founder of the Mindsight Institute, which Siegel calls an action-oriented think-tank. At UCLA, he founded the Center for Culture, Brain and Development, which investigates how cultural and social relations inform brain development, how the brain organizes such experiences and knowledge, and how such developments in turn give rise to a cultural brain. Our cultural practices such as emotional bonds to family or religious devotion are themselves repetitive patterns of energy use that stimulate (from the outside) discernable neural firing patterns and synaptic connections. Our brains become used to, and even develop a preference for, certain patterns, meaning the brain can be trained to behave, and even gradually evolve, based on the activities of the mind.

Technology is helping us shed ever more focused light on which parts of our brain direct specific actions or respond to diverse stimuli. Advancements in artificial intelligence have benefited from such insights, leading to devices which can “read your mind,” i.e. discern signals of will and intention, for example with respect to where you wish to move a computer mouse, and translate that intent into action. By this logic, culture is literally a “state of mind,” a cluster of signals which believers of a certain faith share in common. By extension, cultural evolution is to some extent the mutation of patterns of mental signals shared by groups of people. For this reason, the Dalai Lama has embraced this research, and recently spoke at a prominent gathering of neuro-scientists and educators.

Since brain plasticity is greater earlier in life, Siegel is working with children to test patented new communicative technologies that help to transmit the non-verbal signals and a sense of internal mental experience between young people such that they may develop more accurate and empathetic understands of others. Such devices focus on the pre-frontal cortex where our “mental maps” of the self, others, and collective are developed and stimulated. This part of the brain can’t be fooled: it knows when you are communicating with other human beings versus playing a video game. Digital games distort these mental maps, substituting the evoking of action for inter-personal connections. The result can be stunted emotional development. Not just “Grand Theft Auto” but even Baby Einstein have thus been accusedof warping the mind rather than enhancing it. If Siegel’s work continues to yield positive results, it could make a large contribution towards technology making us more empathetic—and yes, humane—than we think is possible today.

Ayesha and Parag Khanna explore human-technology co-evolution and its implications for society, business and politics at The Hybrid Reality Institute.