More Than Footnotes in Economic History

Before the end of the Second World War, officials from the Allied nations met up at a resort town in New Hampshire to create a new economic order for the coming peace. How exactly this happened is a fascinating story that shows how much personalities and politics could triumph over prudent policy in the 1940s. Could they still do that today?

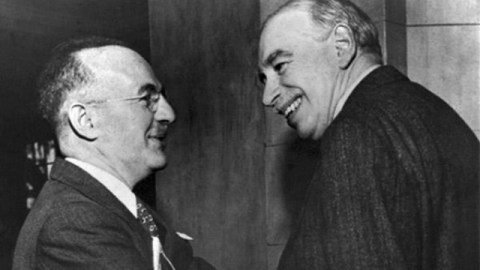

Benn Steil tells the story in a new book, The Battle of Bretton Woods, with particular focus on the famed British economist John Maynard Keynes and an all-but-forgotten American civil servant named Harry Dexter White. The ostensible idea of the Bretton Woods system was to promote stability and growth using fixed exchange rates and two new institutions, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. But Keynes and White were also fighting for their countries’ economic dominance, Keynes’s legacy, and White’s principles.

If you think economics and finance are dry subjects at best, Steil’s book offers a refreshing surprise. It’s a political thriller in which the protagonists, one whom you think you know and one whom you probably don’t, are much more intriguing (in both senses of the word) than they first appear. And it takes place at a time when, as Steil notes, the United States Treasury became a strong arm of foreign policy.

The book also reminds us how similar the economic concerns of the 1930s and 1940s were to those we have today; among the most contentious issues in the years leading up to Bretton Woods was the linkage of China’s currency to the dollar or the British pound. Then as now, economists asked what currency or currencies should be used as the global benchmark for commodities, sovereign debts, and the like.

Even though the monetary mechanism created at Bretton Woods ended in 1971, the IMF and World Bank are still with us today. Yet they have changed in ways their founders did not envision, in part to keep themselves relevant. For Steil, this evolution has positives and negatives.

“Today’s IMF is vastly different from the one envisioned at Bretton Woods, which was only supposed to support a fixed exchange rate system through modest loans to fund short-term balance-of-payments deficits,” he told me. “It was meant to be active in quiet times, not in crises. That said, if the IMF didn’t exist today one would have to be invented. U.S. administrations will always want to have a bailout vehicle at arm’s length from Congress.

“As for the World Bank, it was created to reconstruct Europe after World War II. The Latin Americans, in fact, initially objected to it; they didn’t want their dollars going to Europe. In my view, the World Bank will continue to struggle to convince the world that it plays a meaningful role in economic development; the Asian experience would seem to suggest otherwise.”

With shifts in the global balance of economic power and the way the world does business, it may be time to replace these almost 70-year-old institutions, or at least to add to them. Should there be a global body to regulate polluting emissions? Is it time for a new benchmark currency? How about a mechanism to help countries recover from defaulting on their debts, like a bankruptcy court?

The bigger question is whether two personalities could affect the shape of such institutions as much as Keynes and White did in 1944. Nowadays, corporations bring their interests to bear on policy with monolithic force, and the instantaneous flow of information makes White’s ingenious subterfuges hard to imagine. Moreover, the people who put together economic deals these days are usually technocrats hidden away in the shadows of major summits. And you’d hope that an American president today would have more than “only the foggiest grasp of macroeconomics” that Steil attributes to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

So, could the Battle of Bretton Woods ever happen again? “Personalities still matter,” Steil said. “Think of a Jacques Delors or a Richard Holbrooke. Having said that, we will probably never see a celebrity-diplomat like Keynes again.” That may be for the best, he added, as the involvement of the one of the century’s greatest economists in Bretton Woods ”did not work out well for Britain.”