Man of the Century

Quick Quiz: Who is the only artist to be named “man of the century”? Picasso? Did Demoiselles d’Avignon and Guernica preach love and peace to define the twentieth century? I wish they did, but, sadly, no. You have to go back all the way to the fourteenth century to find TIME Magazine’s “Man of the 14th Century,” as named in their 1999 end-of-the-millennium roundup. By painting people three-dimensionally and more humanly than ever before, Giotto di Bondone started a revolution that no artist has equaled since. Will any, can any, ever top Giotto?

Giotto’s toughest competition for top spot of his century, at least from our perspective, came from his paisan Dante Alighieri and England’s Geoffrey Chaucer. The long list of rulers of the age fail to rise above a mosh pit of feudalism, warfare, and peasant revolts to achieve any level of distinction. If TIME wanted to mix things up, they might have named a “Bacterium of the Century,” which the Black Death would have won hands down. In honoring Giotto, Johanna McGeary wrote, “Giotto fathered a radical revolution of startling genius that set the course of Western art for the next 600 years.” Big words, but Giotto lives up to them, even today.

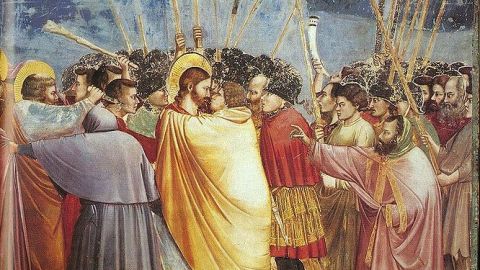

But even Giotto, who died on this date in 1337, came from somewhere. According to legend, Giotto’s teacher, Cimabue, discovered his prize student as a young boy sketching the sheep he was tending. Cimabue was already beginning to paint more realistically than previous generations, but it was Giotto who took the next evolutionary step. Part of the motivation behind that step came from another Italian, a fine candidate for the man of the thirteenth century—Saint Francis of Assisi. Saint Francis brought heaven back to human terms, elevating life on earth by honoring the planet and all its inhabitants. When you look at Giotto’s The Arrest of Christ, also known as The Kiss of Judas (pictured), one of the scenes of the life of Christ in the Cappella Scrovegni you see Francis’ thoughts made tangible through Giotto’s hand. Giotto painted these scenes in the Cappella, also known as the Arena Chapel, early in his career, from 1304 through 1306. When Jesus and Judas lock eyes in the middle of a maelstrom of human activity, we feel the humanity of both figures—the same humanity that Saint Francis restored to a church that he had seen as abandoning the people it was created to serve. In such scenes, Giotto, too, restored religious art (and, by extension, all art) to the people—a gift we still enjoy six centuries later.

Without Francis, we may not have Giotto, as we now know him. Without Giotto, we may not have Francis, at least in the same sense we know him today. The two figures and artists of the human soul work in tandem in our minds even today, silent giants upon which others have built. Looking back at that perfect partnership makes me wonder if philosophy and art could ever connect that way today. The tragic events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have misshapen philosophy and religion into a hopeless hot mess of fundamentalism and despair—not the most useful ingredients for inspiring great art. Picasso tried to show us peace, love, and understanding, but few were ready to look or listen to that message. But the twenty-first century is young, and hope springs eternal for a thinker to inspire us and a painter to show us what that vision can look like.