Beautiful, Dark, Twisted: George Condo at the New Museum

Kanye West‘s album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy came out too late to be nominated for the Grammy Awards being held tonight, so we’ll have to wait until next year to see the master provocateur in action. Those familiar with the cover artwork of West’s album won’t have to wait so long to see more of the art of George Condo, star of the exhibition George Condo: Mental States, running at the New Museum through May 8, 2011. When West specifically went looking for an artist who could stir up a controversy, he found the perfect partner in Condo, whose works fulfill the requirements of dark, twisted, and, most of all, beautiful, but in a haunting, “where have I seen this before” kind of way.

Condo first rose to fame in the 1980s with his “fake Old Master” paintings that evoked legends without slavishly copying them. “Over the past three decades, in canvases that articulate [a] kind of potent and mixed emotional charge,” Ralph Rugoff writes in the catalog to the exhibition, “George Condo has explored the outer suburbs of acceptability while making pictures that, for all their outrageous humour, are deeply immersed in memories of European and American traditions of painting.” Picasso, Goya, Matisse, Rembrandt, Velázquez, Tiepolo—all of these and countless others fall into Condo’s aesthetic blender just before he hits the switch. But what makes Condo’s “fakes” fascinating is that they make us think of these artists without allowing us to connect the “fake” to a master’s original. Condo “is not a painter of appropriated imagery; nor is he a shoot-to-kill hunter of art-historical father figures,” explains Laura Hoptman. “He is more like a philologist—a collector, admirer and lover of languages—in this case, languages of representation.”

A painting polyglot, Condo can seem like a one-man tower of Babel, but the message comes across clear no matter what dialect he’s working in at the moment, usually in the form of a joke. Condo “insist[s] on the intimacy of the rational and irrational as well as the ridiculous and the sublime” and “asks us to put aside the neat categories we use to organise our aesthetic and moral responses in order to glimpse something of that chaos of incongruous and incompatible drives that underlies our scrambled existence” Rugoff believes. “In this moment of recognition we may even experience a kind of ecstasy, or a wicked delight, as the horizons of our own mental state suddenly expand to take in, however briefly, the fragmented fullness of our contradictory world.” Long ago, Condo played base guitar in a punk band called The Girls (which once played the same bill as Jean-Michel Basquiat’s band Gray). In many ways, Condo’s still a punk rocker at heart. Whereas the Sex Pistols sang their subversive version of “God Save the Queen” in 1977, Condo painted two decades later his The Insane Queen, a fractured portrait of Queen Elizabeth II. All the contradictions of the world, heightened by the power and prestige of royalty, come to a head in this twisted head of the Queen of England.

Yet, as Rugoff points out in his masterful examination of Condo, we still connect with the subjects of Condo’s portraits despite their grotesque façade. Portrait subjects such as the Queen, Mary Magdalene, and even Jesus confront us with a direct stare, as if they’re in on the joke, too, and only want to share in the fun, or the tragedy, depending on your point of view. Such a lack of self-consciousness in portraiture sets Condo apart from artists such as John Currin and Glenn Brown in Rutgoff estimation, who followed Condo’s example in a return to figuration but can’t pull free of the gravitational field of art history’s weight the way that Condo convincingly can.

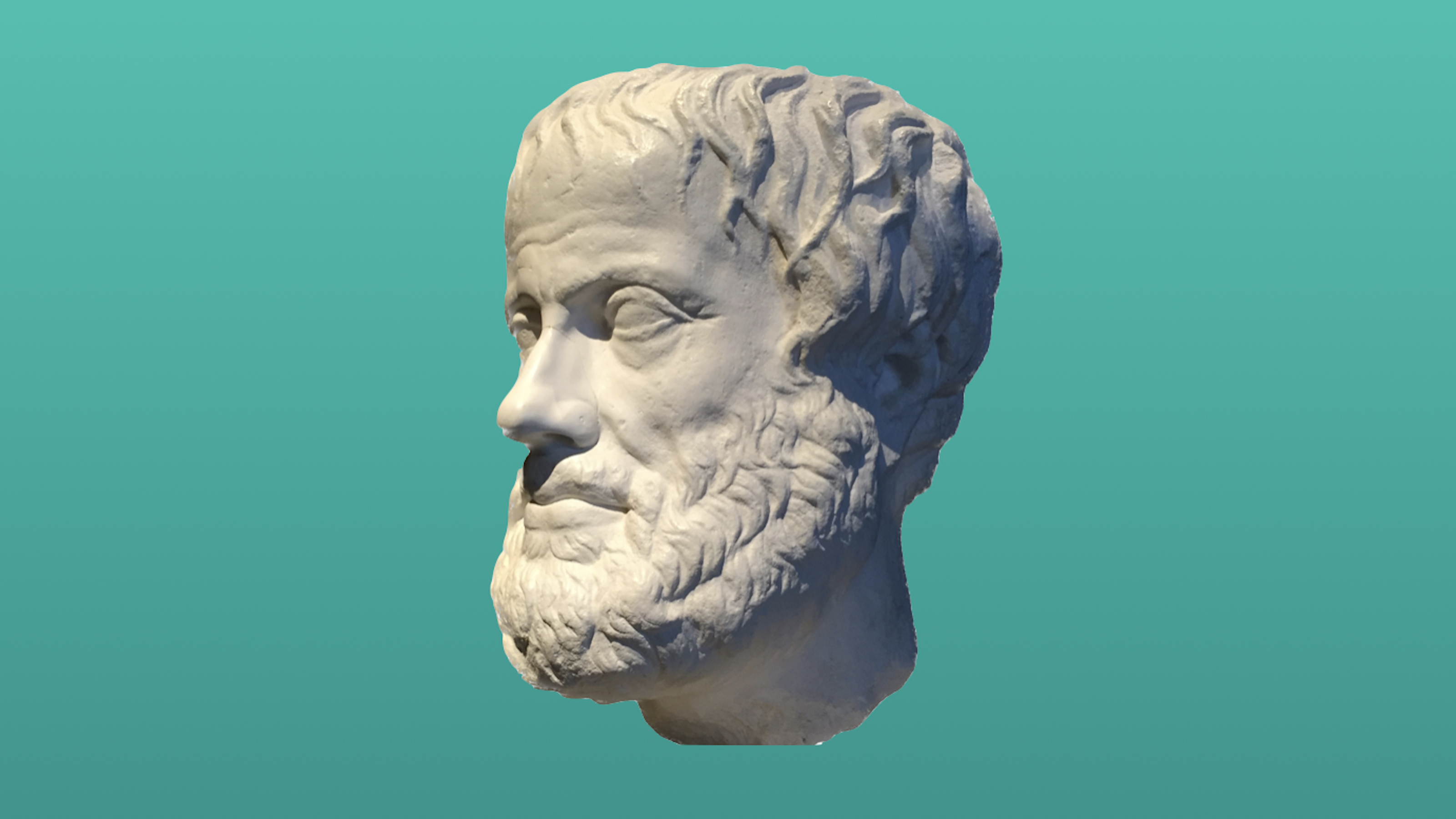

Condo manages this escape through a new kind of figurative abstraction. “For Condo, ‘abstract’ is a verb; rarely, if ever, is it a noun,” Laura Hoptman argues. “The act of abstracting—pulling out and summarising with a curvaceous line or a deftly rendered shape—is evident in all of his work, whether it is in what he calls the ‘physiognomic abstraction’ of the physical characteristics of his subjects in his portraits made over the past decade, or in the Kandinsky or Gorky-like motifs that Condo sees as ‘representations of elements of abstract paintings.’” This merging of figuration and abstraction allows works such as 2010’s Figures In a Garden (shown above) to straddle both worlds without tipping fully into either, creating the same tension between reality and fantasy, between rationality and irrationality, that the portraits convey through their unbroken stares.

“In the beginning, I took fragments of architecture to create a person,” Condo has said of his art, “now I take a person and fragment them to make architecture.” Condo builds skyscrapers of personality from the fragments of art history he’s shored against the ruins of modern existence. If life today seems dark and twisted, making it beautiful requires a mind and eye like that of George Condo.

[Image: George Condo, Figures In a Garden, 2010. Acrylic, pastel, and charcoal on linen, 78 x 108 in (198.1 x 274.3 cm). Collection Laura and Stafford Broumand. © George Condo 2010]

[Many thanks to the New Museum for providing me with the image above and other press materials for the exhibition George Condo: Mental States, which runs through May 8, 2011.]