Only a Monster Never Gives Up Hope

Among the appalling sights Primo Levi witnessed at Auschwitz was the fervent prayer of a prisoner grateful to be spared the ovens. “I see and hear old Kuhn praying aloud,” Levi wrote, “with his beret on his head, swaying backwards and forwards violently. Kuhn is thanking God because he has not been chosen.” Levi was as baffled as he was angry: “Does Kuhn not understand that what has happened today is an abomination, which no propitiatory prayer, no pardon, no expiation by the guilty, which nothing at all in the power of man can ever clean again? If I was God, I would spit at Kuhn’s prayer.” I thought of Levi the other day, watching the Donmar Warehouse’s fine production of King Lear. I’ve never been at ease with the character of Edgar, the “good” son who save his father (twice) from suicide and despair. Edgar has, at the end, an aspect of Kuhn. And Shakespeare knew it.

When you read the play in high school you learn that Edgar is pure and good. With his “foolish honesty,” he’s done out of his inheritance by the schemes of his bastard half-brother Edmund. Hunted for a crime he didn’t commit, Edgar disguises himself as a madman and, twice, leads his blinded old father away from thoughts of suicide. It’s Edgar who believes always that “the gods are just,” and Edgar who says the famous lines “Men must endure/Their going hence, even as their coming hither./ Ripeness is all.” We must, he says, have faith, and trust in good. He never seems to grasp that some abominations shouldn’t be endured—that there is a point where respect for the gods becomes contempt for people. Such true believers may be necessary to see communities through the worst times. But they are, in their indifference to suffering, monsters.

I think it’s significant, then, that when King Lear begins to die before the bodies of all his daughters, it is Edgar who tries to stop him, crying “look up, my Lord.” Aesthetically and morally, Lear has earned this death; he needs to go. Edgar’s act is literally ugly, and his compassion is revealed to be fanaticism. Shakespeare makes the truly noble Kent intervene to stop the commissar of virtue: “Vex not his ghost: O, let him pass! he hates him much /That would upon the rack of this tough world/Stretch him out longer.”

It’s uncanny, as A.D. Nuttall has written, to keep finding that whatever you’ve thought, Shakespeare thought of it first. But there it is. In the 17th century, he seems to have intuited that type of the 20th century religion and politics, the person whose faith is insane, and whose compassion is without mercy.

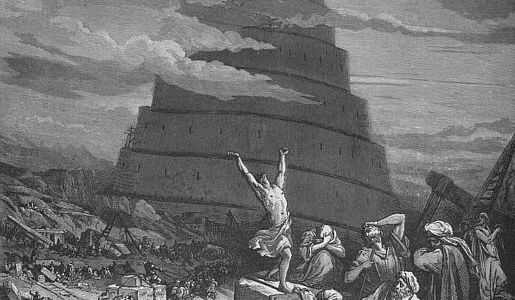

Illustration: Lear and Cordelia in Prison. William Blake, via Wikimedia.