Lost in Translation: Why the Incredibly Mundane Details in the Dead Sea Scrolls Are Important

Piecing together biblical fragments kindles our imaginative fascination that new clues regarding the foundations of Western culture will be revealed, as well as hopes that long-standing assumptions will be overturned. For example, a recent Da Vinci Code-esque mystery involving a former pornographer and Harvard professor led one reporter to spend years piecing together an uncertain narrative about Jesus’s wife.

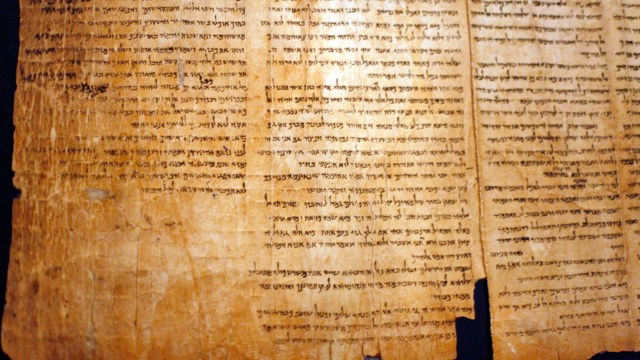

When I was studying religion in the mid-nineties the Dead Sea Scrolls, then referred to as the ‘Q texts’ (discovered in the caves of Wadi Qumran in the West Bank), were all the rage. Though unearthed a half-century prior, evolving technologies offered researchers fresh insights on what Hebrew Scriptures said. It also forced them to question why some texts were left out of modern bibles.

Enter virtual unwrapping. This “3D digital analysis of an X-ray scan” has just been used on a scroll discovered in an En Gedi synagogue on the Dead Sea. As it turns out, the text is the earliest instance of the first two chapters of Leviticus. Researchers were excited to realize the badly damaged scroll reveals a near-verbatim account of Masoretic text.

A screen shot shows the deciphered and original text of what is believed to be a 1500 year old copy of the beginning of the book of Leviticus. The Israel Antiquities Authority has been cooperating with scientists from Israel and abroad to preserve and digitize the scrolls which were discovered 45-years ago during archaeological excavations in Eid Gedi on the western shores of the Dead Sea. Photo GALI TIBBON/AFP/Getty Images.

The Masoretes began copying scriptures in the seventh century, establishing themselves as the authority of Jewish literature. While the King James Version is the default translation for the general public, it only dates back to 1611. Although dubbed authoritative, many scholars disagree.

Leviticus is the third book of the Pentateuch, the laws of Moses. The first 16 chapters are the Priestly Code, transmitting dietary laws that set the stage for Yom Kippur; later chapters, the Holiness Code, involve morals, including sexual conduct such as incest and homosexuality.

The first ten chapters explain to Israelites the proper means for using the newly constructed Tabernacle, a portable temple constructed during the time of the Exodus. Since nomads would not have permanent temples, Leviticus laid the grounds of ritual purity while the land beneath their feet constantly shifted.

If this newly translated scroll is faithful to the Masoretic text, then in chapter one we find the Lord chatting up Moses outside of the Tabernacle about the proper way to sacrifice cattle. Killing the animal helps man atone. The blood, particularly important, is spread around the altar. A barbecue follows, the priests flaying and cutting the bull into pieces.

At that point the sons of Aaron, Moses’s older brother—God could have said ‘your nephews,’ but He has such a flair for lineage—are to arrange the pieces around the fire in just such a manner, to create a “sweet savour unto the LORD.” (God liked capitalization, pre-empting Facebook rants.)

Chapter one concludes with a range of animals being announced: fowls, pigeons, turtle-doves, goats, sheep—He likes meat is the point. Unlike those wicked Mayans, no human flesh on this menu. He repeats that by burning the meat northward and spreading the smoke it is a “sweet savour.”

What’s a barbecue without seasoning? Chapter two kicks off with a sprinkling of fine flour, oil, and frankincense. More sweet savouring. Unleavened bread is next, where the oil is used to bake the wafer on a griddle. Five graphs are used to reaffirm this point, along with the fact that leaven and honey are blasphemous. They do not inspire sweet savour. Amazingly, in graph twelve, we discover that God’s naturally sugary desserts are not sweet enough for Him:

As an offering of first-fruits ye may bring them unto the LORD; but they shall not come up for a sweet savour on the altar.

With all the focus on sweetness, in the next directive God reminds his sacrificers that salt is required of all offerings. No mention of umami, however.

Chapter two ends with yet another recipe item: groats. Apparently God was into whole grains even back then, though we are left to question his true feelings on gluten—why no leavening? As with so much else, God works in mysterious ways.

Thus concludes this instructive discovery, one in which Dead Sea scrolls expert Emanuel Tov proclaims, “We have never found something as striking as this.” And he is right. While today looking back at God’s clamoring over sweet savours is amusing, at the time it was a necessary response by an oppressed peoples. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jack Miles explains:

Leviticus, obsessed as it is with a holiness and purity that begin quite literally with the physical land itself, does not intend to accommodate on that land the polluting worship of foreign gods.

The traveling Tabernacle, and the rules for engagement within, inform the tribe’s identity, the very thing they were most afraid of losing—something we witness in societies around the planet today. Purity has always been a critical religious component; it separates tribes. While membership remains strong due to these rules, it dehumanizes others: those bread leaveners are committing acts of blasphemy. Leviticus, even with its contradictory take on foreigners, kicks off with painstaking instruction on how to separate Israel from other nations, especially its oppressors. In truth, more survival technique than Shabbat menu.

Which does make one agree with Tov’s assessment. If this new scanning technique allows scholars to read nearly destroyed texts, many treasures are on the horizon. This particular victory reaffirmed an authoritative source text. In the future who knows what could be upended and reconsidered?

—

Derek Beres is working on his new book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health (Carrel/Skyhorse, Spring 2017). He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.